Do you remember the first music you ever bought?

Whether it was a digital download, a compact disc, cassette, eight track, or a 33-1/3, 45, or even a 78 RPM wax record, I’ll bet you know that first song or album by heart.

Mine was way back in 1967, The Monkees’ Headquarters album. My parents bought it at the neighborhood pharmacy, believe it or not. I played it over and over and over again. I would have kept playing it, but my little brother, Ira, the future disc jockey, took a bite out of it, literally. I still have it though.

No matter what kind of music you like, whether it’s Bruce Springsteen, Lawrence Welk, or Gwen Stefani, we all form attachments to our favorite songs. For example, the first song my wife and I danced to at our wedding was Springsteen’s “I Wanna Marry You,” and it still brings a smile to my face almost 20 years later.

The point of these anecdotal snapshots? Music matters in our lives.

But the music industry itself is undergoing a historic shift away from the sale of physical albums to downloads of music, one 99¢ song at a time.

Where is pop music going? That’s the topic of today’s interview with Tamara Conniff, Billboard editor and associate publisher , where she oversees all aspects of the Billboard brand, from editorial to face-to-face events. She is the youngest person and first woman to hold this post.

Prior to joining Billboard, Conniff served as the music editor for The Hollywood Reporter for five years and was senior editor in charge of music for Amusement Business. Her work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Los Angeles Daily News, the Boston Globe, and the New York Post, among other places.

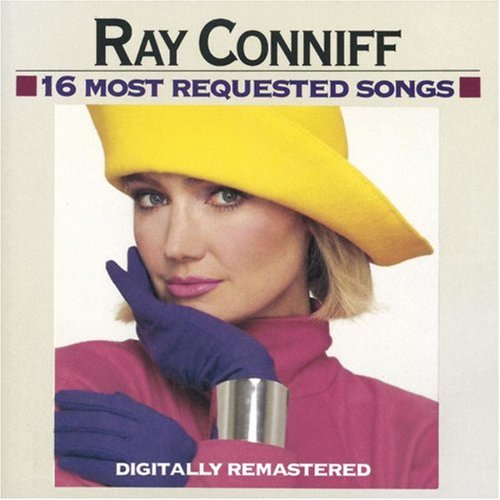

Born and raised in Hollywood, she is also the daughter of the late American music legend, Ray Conniff.

Tamara Conniff Website • Artist Publishing Group • Twitter • LinkedIn • TheComet.com • Ray Conniff: 16 Most Requested Songs-Encore! from Amazon.com

BOB ANDELMAN: Let me ask you: is “American Idol” the greatest thing to happen to the music industry since Ahmet Ertegün, or is it the worst development since Milli Vanilli?

TAMARA CONNIFF: Ah, I think it’s a little bit of both, actually. What’s interesting is industry observers during the first season of “American Idol” — when it first started — we were convinced that it was going to be dead in the water. And here we are multiple seasons later and millions and millions of albums sold.

I think what “Idol” really does represent is the shift in the music industry, of a texting-oriented generation. “American Idol” really sort of ushered in the whole text voting, which translates to ring tones and purchasing music with your mobile phone. It also really showed the marketing power of television over traditional media, like radio. It showed that shift in music. I would say that out of all the Idols, there are three breakout stars — Carrie Underwood, Jennifer Hudson, and of course, Kelly Clarkson are actually really fantastic singers. Is it teen sugar-pop at its best or worst? Absolutely. Has it affected the ability for young artists who do not have that kind of exposure to get signed and be promoted? Yes.

ANDELMAN: In a positive or a negative way?

CONNIFF: Negative.

ANDELMAN: Really?

CONNIFF: Oh, yeah.

ANDELMAN: You think it’s closed doors?

CONNIFF: It has absolutely closed doors to a lot of artists in the business. The one question that record label executives ask themselves is, when they sign a young artist, “How do we break them if they don’t have a platform?” “American Idol” is a platform, you know. How they would normally do it would be to promote it radio, do a couple of radio shows, maybe do a mall tour depending on the age, But now, those avenues don’t hold the power, so unless you have television, either “American Idol” or maybe “Grey’s Anatomy” or one of the hit shows really championing your artist, it’s very hard to take an unknown artist and break them.

ANDELMAN: Wow. So would you say as those doors have closed, has the industry also gotten a little lazy?

CONNIFF: I don’t think it’s laziness as much as it is fear. In your introduction, you talked about the first album that you had in 1967. You look back at the ’60s and the ’70s, record companies were independent. A&M was an independent company. They weren’t owned by the conglomerates who are forcing record executives to meet quarterly numbers. The music industry isn’t like making cereal. You never know when you’re going to have a hit or not have a hit. EMI was late releasing the Coldplay album, and their stock plummeted. You know, back in the day, those issues weren’t a concern to music companies. They’d wait for years for the record to come out.

ANDELMAN: Right.

CONNIFF: So it’s not laziness as much as it is fear and trying to find something that’s going to help you meet those numbers.

ANDELMAN: Has the industry also come full circle in the last 40 years? In the ’50s and ’60s, even the ’40s, for that matter, it was really a singles industry. There were albums, but people were buying 45s and single songs, then we went through these years of the rock albums, the whole concept and the album, you’d be buying a whole album. There was album radio, and now we’re really at that point, aren’t we, with the 99¢ downloads, and some new artists aren’t recording a whole album, they record a song, and if they sell enough copies, maybe then they get an album.

CONNIFF: Well, the interesting thing is that it was really the record industry that kind of screwed themselves on this one.

The record companies actually took singles off the market about 15 years ago, and the reason why they did that is because singles were cannibalizing record sales. People weren’t buying the $12 album, they were buying a $2 single, so the record companies thought, “Hmmm, why should we offer singles and they are not buying the album? We’ll force them to buy the whole album for the single.” So they were releasing at that time a lot of albums that were a whole lot of fluff with one strong song, and the consumers had to pay $12 to get that album This was also during a time when soundtracks were very successful, because soundtracks are essentially a collection of singles.

So what happened with the advent of that technology and the peer-to-peer sharing technology is the consumer got really smart, and said, “I’m paying $15 for an album that sucks because I like one song. Here’s this new service; I can go get it for free.”

ANDELMAN: Well, I agree with that completely. I know the reason I stopped buying records was I was just sick of having to spend that much money, and really all I wanted was one song.

CONNIFF: Right. So you’re looking at a situation where it is a singles market, again. Absolutely, but that’s because of how record companies have been making albums and also because of technology.

ANDELMAN: How far can the “American Idol” approach go? It’s still drawing like crazy. As we’re talking, they are winding up what I guess is the sixth season, and I read where they’re talking about spinning off a show that is band-oriented, and of course, we have “RockStar,” the Mark Burnett show, and “Dancing with the Stars,” which is just kind of a variation, more focused on dance but heavy music. How far can all this go? Will we have more programs? Will we sell more records this way, or will it have to start to swing back at some point soon?

CONNIFF: At some point, everything swings back. Everything has a life cycle as pop music has a life cycle. I mean, you can go back to the real sugary, doo-wop of the ’50s, which is in no way dissimilar from ‘N Sync or the Backstreet Boys. I think that this phase will pass, and then another phase will begin, and then probably another 15, 20 years from now, we’ll go back to pop music, and we’ll have another “American Idol,” which in many ways is sort of like “American Bandstand” except for the voting aspect of it. It’s all cyclical, I think.

ANDELMAN: We’ve talked a little bit about what may be wrong with the industry at the moment. What’s right about the music industry? What can it brag about? What’s it doing right today?

CONNIFF: That’s a very good question.

ANDELMAN: I was afraid from your brief silence that there was no answer.

CONNIFF: I actually have to think about what they’re doing right. They are actively embracing new technologies, finally, even though they’re a little late. Some of the companies, EMI being the forerunner, have said goodbye to DRM.

ANDELMAN: Digital rights management.

CONNIFF: Digital rights management, which is a big plus for consumers.

ANDELMAN: Do you think other labels are going to follow it because it’s the right thing to do or because it’s their opportunity to get an extra 30 cents a song for downloads?

CONNIFF: I think you have to do it. I’m kind of opinionated about this, but DRM is sort of like Reagan’s Star Wars, you know. Like, what are you doing? Essentially, you are punishing consumers who want to buy music by making it impossible for them to use it on the devices they want to use it on, and the people who are going to steal it are going to steal it anyway. So I think that DRM was a huge waste of money, and it’s torture to consumers who seek to buy music legally. I think eventually all the labels are going to have to abandon it.

ANDELMAN: Does the fact that its EMI reached this deal with iTunes… iTunes was already standing high apart from everyone else. Does it now put someone standing on its shoulders making it that much harder that anyone will ever catch up to it?

CONNIFF: I don’t know. The irony about iTunes and their DRM strategy is that they were like the worst culprits of DRM with the rights management drowning iTunes.

Listen, I think that they had to do this in order because other media players were actually starting to chomp at their heels. I don’t know. I think that it’s a cultural phenomenon, Apple and iTunes, is, and at some point, it will swing again, but I don’t see it stopping any time soon.

ANDELMAN: This is a little broad of where we’re going, but has the Zune had any impact in the market at all?

CONNIFF: Zune is a really fantastic product. The only problem with Zune is that not enough people have it for it to work. Zune is a sharing system, and in order to share, you have to have someone who has a Zune, so the problem is that it’s not mass market yet.

ANDELMAN: Do you think it ever will be?

CONNIFF: I think if they stick to it and continue to adapt it and make it smaller and find a right promotion for it, I think that it could be a viable competitor. But it was a very advanced product to come into a market that wasn’t really ready for it.

ANDELMAN: As you were saying that, I was trying to remember the last time I saw an ad either on TV or in print for the Zune, and I honestly can’t remember.

CONNIFF: Yeah. I think that they’re going back to the drawing board a little bit for the next incarnation of it.

ANDELMAN: So we talked about “American Idol”’s impact on the industry. What about iTunes and Apple? Have they played a big role in revolutionizing the music industry?

CONNIFF: Well, yeah, absolutely. Good and bad, I suppose. They have made music portable. They have made downloads legal. They have become a huge marketer of music. They’ve definitely steered people away from peer-to-peer sites where it was free to pay for music. The only problem is that they have also set a price point that is 99¢, and that’s a pretty low price point to start from. It’s hard to lower that. I think it would have been better for the industry to start it a little higher.

ANDELMAN: Of course, there has always been this belief in retail that you want to be under the dollar, whether it’s $9.95 being under $10 or 99¢ being under $1.

CONNIFF: Absolutely. But as you see the value of music going down, the monetary value of music going down, you might have wanted to launch it at $2.99 to have negotiating room, to bring the price down.

ANDELMAN: How much impact has iTunes and iPods and for that matter, Zune and SanDisk, how much impact have they had on radio, because I know that Billboard covers radio, as well.

CONNIFF: Well, radio, it’s not only that so much, I think the Internet has had the biggest impact on radio.

ANDELMAN: How so?

CONNIFF: With web radio, with bloggers being able to do play lists with web casts. On the web is where you find the old-school DJs or what we remember as DJs, where you find a community and someone whose taste that you like, and you go, and you listen to their playlist. That’s what DJs used to do. So I actually think that Internet webcasting and Internet radio have been the biggest Achilles heel of terrestrial.

ANDELMAN: That as opposed to satellite radio.

CONNIFF: Satellite radio is a totally different demographic. Your average kid can’t afford satellite radio, nor do they care or are they going to buy it. Satellite radio is for an older consumer, and it certainly has been positive, but I don’t think it’s really taken that much away from terrestrial.

ANDELMAN: Let’s come back to the music industry. Among the major labels, and even what few independents there are, whose star is rising these days and whose is falling?

CONNIFF: On the label side?

ANDELMAN: Yeah.

CONNIFF: You know what? The indies are definitely on the rise. You look at a number of indie labels and indie distributors and so many indie releases that have come out. Koch is definitely hot right now. Victory Records always has some great hardcore rock fans. Even Sub Pop is sort of having a new revolution since the grunge era in signing artists. I think a lot of artists are opting to go in indies because the deal terms are better. The advance money isn’t as big, but the deals are better, and the rights are better. The other thing about the indie labels is that they are much more nimble and able to adapt to changing technology much faster than the big conglomerates who aren’t. So if I were an artist today, I would definitely look to go with an indie.

ANDELMAN: It seems like there has always been an opportunity in music for independents to rise up. I just read a book, I think it’s called Machers and Rockers, about Chess Records. That was a great example of it. You know, who’s this guy Chess? Where he’d come from?

CONNIFF: Right.

ANDELMAN: Sub Pop Records, of course, with the whole Seattle, as you mentioned, the grunge, and there has always been that opportunity. So where does this leave the major labels today? They’re merging, and they’re eating each other alive. Are any of them doing it right?

CONNIFF: Very interesting question. I would say that probably the people who are furthest along the right path is Warner Music Group, mainly because they’ve been forward-thinking about technology. And while they’ve had a lot of layoffs, they really trimmed fat and focused on smaller rosters that they can work better as opposed to over-signing. So I think that Warner is probably, in terms of technology, Warner is a forerunner.

Universal Music Group is, of course, the largest, and each label within the Universal Music Group system is very different, and certainly all of the Universal labels have probably among the best leadership in the business. We’ve got Jimmy Iovine at Interscope. A&M/Geffen is brand-oriented and big picture. L. A. Reid, who’s a music guy through and through who’s taking care of Island/Def Jam. So you’ve got good people in place, it’s just the economics are difficult. Here’s the best way I can explain it. Ten years ago, the number one album in the country sold, I don’t know, like 2.5 million albums the first week. In January 2007, the number one album sold 70,000.

ANDELMAN: I wanted to ask you about that. It is astonishing the change in what’s considered a big hit album right now compared to a few years ago.

CONNIFF: Oh, absolutely.

ANDELMAN: The buying public’s tastes have become that diffuse, I guess, because they have so many options.

CONNIFF: No, I don’t even think it’s that. There is a whole generation of consumers out there that have never, ever, ever bought a CD. It’s like completely foreign to them. “A CD? Why would I buy a CD? I’m going to get that off iTunes, or I’m going to get it from a peer-to-peer service.” They just have no concept of buying a physical product, so they’re buying the music, they’re buying the ring tones, they’re buying the songs, they’re just not buying it on a physical disc.

ANDELMAN: I don’t imagine my daughter, who’s 10, ever buying a CD or whatever follows it, whereas, we’re still buying the occasional DVD, and of course, there used to be VHS tapes for her. She’s been able to download music for the last two years. Why would she want to do anything different?

CONNIFF: Yeah. It’s a waste of space.

ANDELMAN: Speaking of downloading music, still, what’s holding up at this point The Beatles and EMI from getting their music into the digital era?

CONNIFF: Rates. It’s cost. It’s rates.

ANDELMAN: They want more money for it.

CONNIFF: Yeah.

ANDELMAN: That’s all it is?

CONNIFF: Yeah.

ANDELMAN: So at $1.29, the deal that EMI struck, do you think it will happen?

CONNIFF: I think it will. I think the Beatles are very perceptive over their music and are not going to give it away cheap. It is the most popular music in the world, and there is no reason for them to give it away cheap.

ANDELMAN: Is there like a bell-shaped curve on this, though, at some point, if they wait too much longer, do they become irrelevant?

CONNIFF: No.

ANDELMAN: Really?

CONNIFF: I don’t think so.

ANDELMAN: Be interesting to see.

CONNIFF: I mean, I honestly don’t think so.

ANDELMAN: Okay. There are kids my daughter’s age who, the name “The Beatles” means absolutely nothing to them.

CONNIFF: Yeah, but they also are discovering you can still stream Beatles music, so I’ve actually found that more kids are actually discovering The Kinks and The Monkees. How would you even know them, and they find them online.

ANDELMAN: Right. But every day, every year, there is so much more music out there to discover. When I was her age, it was the music from the ’50s and ’60s. Now, it’s the same type of music, it’s the ’50s, the ’60s, the ’70s, the ’80s, the ’90s, and the ’00s, so I wonder if they will discover it the same way they might have a few years ago.

CONNIFF: I think so.

ANDELMAN: Let’s turn to your own publication. How has Billboard changed in the last couple years, and how will it be different, let’s say, four or five years from now?

CONNIFF: Billboard has changed dramatically over the past three years. For many years, Billboard is 113 years old, and for many years, it was, let’s say in the past 15 years, it was a very true reflection of the recorded music industry, where it had its head in sand about technology. It wasn’t evolving where things were evolving in much the same way the record labels were not. And as a result, we went through kind of rough patch, because no one was really reading it. It wasn’t that interesting to read, which had to do with a lot of different things. You take a trade publication, you take a particular style of reporting, you take an industry that’s downsizing in panic, it was sort of like a tipping point, I think. Or a sea change or a perfect storm, one of those buzz words, and so I came on with Billboard three years ago at a point where it either needed to change drastically or it was going to continue to go down, and we redesigned it 100% where it actually, even though it is still a business publication, it looks like a consumer publication. My theory on that was, this isn’t your daddy’s trade pub, so it doesn’t have to look like it. It can still have the information in it, but we’re in the music industry. This isn’t Progressive Grocer.

ANDELMAN: Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

CONNIFF: No, and Progressive Grocer is a sister publication; I say that with a lot of love. And we also adapted our coverage dramatically in that we started covering the real music business, which includes advertising agencies, all technology companies, branded entertainment, everything that you can possibly imagine where music is, television, film. My theory, my mission, I guess, was I wanted Billboard to be a place where all these different energies could meet and understand each other better.

I think one of the biggest hurdles of technology and music is that they are very different breeds of people, and they don’t always speak the same language. I kind of use Billboard as a translator tool. This big technology has come out, here’s what it means to the music business. The music business can go, “Oh, okay, this is what the technology means.” Or, I can explain how contracts work or how deals are struck, or the interest of the record label is that if they’re going to give a single, it has to be part of their overall strategy for an album. They can’t just like give it to you, which a lot of technology companies thought they could do.

We are ahead of the curve instead of on top of it, which is key. Our readership has gone up substantially. At a time when print is considered a beast, our print is stronger than ever. and we also developed, we have a half dozen products, such as a mobile application where you can get Billboard information on any device you want.

ANDELMAN: Any trade publications that you kind of look to at this point, three years on, and want to emulate further or that you admire?

CONNIFF: I think when I was looking at the redesign for Billboard, one of the magazines I looked at was BusinessWeek, how they organized information, the issues they addressed, the signs, the ease of use, the covers. I mean, Billboard hasn’t had covers since 1930, and we now have covers again. It’s very difficult to have a trade publication have a cover. Trades are generally newsprint on the front cover, so I really did look at BusinessWeek as sort of a model.

ANDELMAN: It’s a good model. They’ve won a few awards. I know you guys won an award recently.

CONNIFF: I know. It was so exciting. We actually won an Eddy. We’re a 100-plus years old, and we’ve never won an Eddy, so I’m very excited.

ANDELMAN: That’s very good. Now, before we wind up, I have to ask you, I told a story about growing up in my unspectacular house. I have to tell you that I am very curious to know what it was like to grow up in the Conniff family. Was there a lot of music?

CONNIFF: I consider myself one of the most blessed humans on the planet. Whenever anyone asks me, “Is Ray Conniff your father?” and they say that they’re a fan, I always say, “Yes, and I’m proud, and his music is fantastic, but the most important thing about his life is that he was a great father and a great husband.” He was truly a family man.

It was always exciting, I guess. Growing up, obviously, music was always in our household. My father was recording up to two albums a year for a long period of time. Later, he went on to doing just one album a year. He toured once a year, and he would take the family with him, so we’d go touring in South America and be treated like rock stars. And then we’d come back to the United States, and our family vacations were taking my mom, my dad, our animals, and me and packing us into a motor home and driving across the country. That was our family vacation. My dad was happiest when he was wearing jeans and climbing underneath the motor home. I had a great upbringing, and I was lucky that my dad taught me a lot about business, taught me everything I know about the music business.

ANDELMAN: Really? Okay. See, I wondered about that. Obviously, you’re covering music as opposed to making music, which some people might have thought would be a natural progression. Can you play any instruments? Are you musical at all?

CONNIFF: I started playing piano when I was four. I actually played with my father on tour, and I played on albums with him. I never wanted to be, I mean, I am a musician, because I’ve played or studied, but I never wanted to be a performer. I always wanted to be a writer. I think everyone has their calling, and writing was my calling. It’s ironic — I actually had no intention of being a music writer, I wanted to be a political writer. Bizarre. I guess it’s the same thing, sort of. You’re attracted to what you know, and I guess these opportunities just kept coming up for me, and it’s what I know. If there is anything I know on the planet, it’s the music business. You end up writing what you know, and it sort of happened that way, and I couldn’t be happier.

ANDELMAN: We’re coming up on I guess what will be the fifth anniversary of your dad’s passing. I assume that the Conniff family has a personal interest in music rights and royalties, that kind of thing. What do you think will be the music that your dad will be most remembered for and that will be the most enduring?

CONNIFF: It’s very interesting. I’ve been having interesting conversations about my dad’s music. A lot of young kids are discovering it on the Internet and are really into the sort of jazzy, hi-fi kind of stuff. I think what my father will be remembered for is as the brilliant arranger that he was, and he will be remembered for the stuff he did with Artie Shaw. I think above all, he will be remembered for, he created the sound, that he was the first to put voice and instrument together in the way he did. There are many people who followed, but he was the architect. He was also the first person to ever perform in stereo.

ANDELMAN: Oh, really? I didn’t know that.

CONNIFF: Yes. And the first Western artist to go to Russia. And amazingly enough, I think there’s also a big legacy for him in young composers. There’s not a young self-composer I’ve met who’s not been inspired by my father’s arrangements, so I think that it’s a great legacy, and I aspire to take good care of him and keep his music alive.

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

Leave a Reply