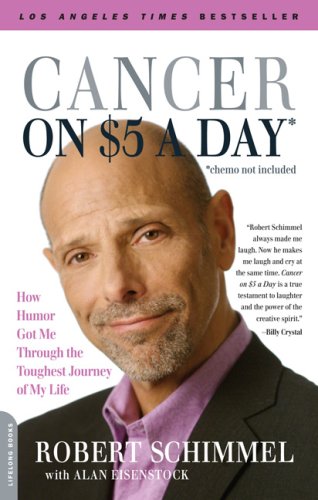

Today’s Guest: Robert Schimmel, comedian, author, Cancer on Five Dollars a Day (chemo not included): How Humor Got Me Through the Toughest Journey of My Life

I tried my hand at stand-up comedy twice in college, once as a freshman at the University of Miami and again a year later at the University of Florida. And no, I wasn’t so bad at Miami that I was asked to leave. They were a lot more subtle than that.

Anyway, I gave up that dream early. It’s a tough, humiliating life, not for me.

Now, Robert Schimmel, on the other hand, is one of the best stand-up comedians of his generation. He, like Richard Belzer before him, is the guy other comedians watch and measure themselves against. He is naturally funny and naturally crude, rude, and not recommended for listeners under the age of 18.

That’s my way of saying if you’re too young to drink or if you’re easily offended, tune out now. The button-down mind of Bob Newhart this definitely is not.

These days, Schimmel is still out doing his job making people laugh, but there is a twist. In 2000, when his career was reaching new heights, he was diagnosed with Stage III non-Hodgkins Lymphoma, cancer. Not good. But he underwent aggressive therapy and routed the disease, even discovering a new source of material for his act in process. And he’s written a book, Cancer on $5 a Day: Chemo Not Included, How Humor Got Me Through the Toughest Journey of My Life.

ROBERT SCHIMMEL podcast excerpt: “I did find humor in it. When you’re in the hospital and you lose all your hair and everything, and your doctor comes in and says, “Would you be interested in a wig?” And he has like an 8 x 10 like a binder, a notebook with different headshots with wigs on them. I said to the guy, “Do you have one for my crotch?” And the guy says, “As a matter of fact, we do,” and he showed me pictures. I almost fell out of the bed. And he said, “Robert, they’re virtually undetectable,” and I’m thinking, Undetectable? I don’t have one eyelash, and then I’m gonna have a shrub between my legs, and that’s not gonna be detectable?”

BOB ANDELMAN/Mr. MEDIA: Robert, I’m kind of curious. You’ve written your first book. What was it like to see your material in such a permanent format? You’ve done CDs, and, subject matter aside for the moment, it’s Robert Schimmel’s voice on paper. What was that like for you?

ROBERT SCHIMMEL: It was hard. I never had any intention of writing a book before because I have friends that are comedians that have books out and basically what their book is is it’s like their stand-up act that’s been transcribed and put into a book. And I never wanted to do anything like that because I know that there are some jokes that you can tell live on stage, and maybe it’s your delivery or your timing, your personality where all those things play into the way the joke works, and you look at it on a piece of paper, and it’s not the same thing.

I used to write for “In Living Color.” There were sketches that you’d write that you knew were funny, but other people read them on a sheet of paper, and they go, “Naah, we’ve got to punch it up a little bit,” and it was perfect the way it was the first time.

I had somebody help me write this book. I’m not gonna deny that because I respect writers, and they usually don’t get any credit for when they help somebody else, but I have a picture of the guy in the inside flap of the book. His name is Alan Eisenstock, and the reason why I chose to have him help me was twofold. One, he interviewed me in 2000 when I was on top of the world career-wise for a Father’s Day issue of Variety magazine, and as we spoke, it wound up us getting kind of close, and he found out that I’d lost a son in 1992, and I found out that he lost a son. So when they offered me the book this year, I wanted to find someone that could help me because I knew that I wanted to have somebody else that shared that same experience as I did because they could help me express myself and maybe in some words that might not be in my vocabulary or a way to say it that I don’t. I also wanted someone that didn’t go through cancer the way I did because I wanted them not to be in my shoes for that because then he could be a good judge.

I can talk about what I went through and some of the procedures and tests and all these other things, and to me, it’s like I might as well be reading a menu to you, but I talk to other people, and a lot of people get overwhelmed and they’re like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, don’t tell me anymore!” So I needed someone to say, “You know what? You’re getting too heavy here, and you kind of said this in this other thing.” He helped guide me into putting it in order and making sure that the book was still light-hearted. That’s why I chose the title, Cancer on $5 a Day: Chemo Not Included, because I wanted people to know right up front that I’m not Deepak Chopra or Dr. Phil and that I am a comedian. This is about cancer, but there are light-hearted moments in it.

The only other choice I had for a title…They wanted something like My Unplanned Journey, which that’s not me, but the other title was When Bad Things Happen to Seemingly Good People, but I like Cancer on $5 a Day. I think that that grabs you, and you look at it, and I’m very proud of it. I really am.

First of all, it’s dedicated to my son, and I’d been waiting ever since that happened to find something that I can dedicate to him and leave that mark even after I’m not here anymore. And if people read this or someone reads it, and I know that people have heard my story before cause I talk about it on stage, if it gives somebody hope or inspiration or go wow, he’s seven years out from what he had, and I just started treatment now, I can do it, then what I went through wasn’t for nothing.

I get to do what I love doing the most, which is make people laugh and entertain them and maybe touch them in a way that can help change their lives for the better, and I do believe that laughter is very healing, not only for the people laughing but for the people on the receiving end of the laughter, too.

ANDELMAN: I have to say, as a guy who makes his living co-authoring books, that it was very nice, not only to hear just a minute ago you give Alan Eisenstock credit for helping you with this, but he actually wrote the introduction to the book, which was very touching in and of itself. It’s very unusual that way.

SCHIMMEL: Yeah. I know he’s written other books for a couple other comedians he’s worked with where he told me that those guys never mention his name, that he’s gone to book signings with them where they don’t even acknowledge he’s in the room, and I just can’t do that. Maybe it’s because of what I went through versus somebody else where they’re just a comic, and they have a book out for something. I admire what he did, and I respect him, and he deserves the credit for what he did. I can’t lie and tell people that I did it all by myself cause it’s not true, and I just wouldn’t do it. And I mention him on the radio. I did now. Every interview I do, I bring his name up. I don’t see what’s wrong with it, and I can understand why writers would want to strike, and when they don’t get the credit that’s due to them because this guy basically had to go back into his own feelings about losing his child.

We sat together for days and days and days. Every week, we got together like 3, 4 days a week at Taverna Tony, this Greek restaurant that’s in Malibu, and it’s like halfway between where he lives and I live. There were days that we were laughing. There were days when we were crying where we just had to stop, and we said we couldn’t do anymore that day because he started talking about things about his son, I would talk about mine, and then that was just it. And we knew that we weren’t going to get anything done that was going to be able to get on paper that day.

So for him to do that, to me, that’s not just sitting down and writing a book with someone or transcribing or re-writing. He emotionally took that roller-coaster ride with me, and it’s a tough ride to take. It really is.

I didn’t want to write about my son in the book, and I’ll tell you why. It’s so bizarre. I only want to have a positive effect on people with this book, not negative, and the fact that my son lost his battle, I didn’t want to put that in anybody’s head. I very rarely talk about my son in my act onstage unless it’s a fundraiser for a pediatric oncology thing. Otherwise, I don’t. I don’t want to use what happened to Derek… I don’t want to exploit what my son went through to elicit a certain response from the audience because honestly, I told Alan, “We both have the ultimate trump card. I could go onstage and bomb, and people can come over or the owner and say, ‘You really stunk,’ and I could say, ‘Yeah, yesterday was my son’s birthday and he would’ve been…’ That’s all you gotta say, and you’re off the hook right there, and I just won’t do it.”

There are people that don’t make it. I want to be realistic also, but life is still beautiful no matter what. My life is as precious as his was, and I have other children, and I just didn’t want them to feel like second-class citizens to him. What would they have to do? Get really sick before they get the attention he got? And I did find humor in it. When you’re in the hospital and you lose all your hair and everything, and your doctor comes in and says, “Would you be interested in a wig?” And he has like an 8 x 10 like a binder, a notebook with different headshots with wigs on them. I said to the guy, “Do you have one for my crotch?” And the guy says, “As a matter of fact, we do,” and he showed me pictures. I almost fell out of the bed. And he said, “Robert, they’re virtually undetectable,” and I’m thinking, Undetectable? I don’t have one eyelash, and then I’m gonna have a shrub between my legs, and that’s not gonna be detectable?

ANDELMAN: Now wait a minute. Did you actually buy one, though?

SCHIMMEL: Of course I did.

ANDELMAN: That’s what I thought, yeah.

SCHIMMEL: Of course I did, and it looked so stupid. It looked like a hair donut. It was like a Krispy Kreme donut that somebody dropped on a barbershop floor, and my wife wouldn’t even play ring toss with me.

ANDELMAN: Now, did you buy a wig for your head, though, for the top of your head?

SCHIMMEL: No.

ANDELMAN: No, but you bought one for your crotch?

SCHIMMEL: Yeah, well, because I was losing my hair already before chemotherapy, and I was thinking if I walked out of the hospital with a full head of hair, people would go, “What, are you kidding?” That was already gone way before chemotherapy.

ANDELMAN: Right.

SCHIMMEL: I do believe that attitude has a lot to do with overcoming obstacles in your life. When I first got diagnosed, my doctor came in the room, and I thought I had the flu. I was working in Las Vegas at the Lance Burton Theater at the Monte Carlo. It was June 2 and 3, 2000, coming back from the from shopping with my dad, and I’m freezing, and I say, “We gotta stop. I gotta get a sweatshirt or something. I’m shivering.” And he said, “Bob, it’s like 112 degrees out.” And I go back to my room. Like an hour before the show, I’m getting the chills and sweats, and I go into a hot shower that was so hot my dad couldn’t believe that I was standing in there, and I still had goosebumps, and my teeth were chattering.

I thought it was the flu. And I felt tired, I was losing weight, I go to the doctor, they find a little lump, they go and do a biopsy, and even after what I went through with my son, cancer was the furthest thing from my mind. I would think that that’s not gonna happen two times in my immediate family. And when they told me, the guy came in, I was with my mom and dad and my wife, and he had a legal pad, and he drew down the center a line. On one side, he wrote “Hodgkins Disease.” On the other side, he wrote “non-Hodgkins.” Then he wrote “aggressive, indolent, Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, Stage IV,” and all this stuff, and he said, “Robert, I wish I could tell you that you had Hodgkins Disease, but you have non-Hodgkins.” And I said, “You know what? That’s just my luck. I got the one that’s not named after the guy.” And he laughed, and he said, “You know what? You’re gonna be okay.” And I said, “I am?” And he said, “Yeah, cause your head’s in the right place.”

And I’m not saying I wasn’t scared because I was.

It got to a point right before the last treatment where it’s like you’re thinking, If this didn’t work, I don’t know what would happen to me mentally. Only so many things can happen to you before you just start laughing because that’s the only thing left to do is laugh. It really is.

My parents are Holocaust survivors. My dad’s parents and his sister and brother were shot in front of him and killed, and he’s the sole survivor of his family and went to Auschwitz. My dad has the greatest sense of humor I’ve ever heard. He never is negative. As a matter of fact, when Derek got diagnosed, he said, “Robert, don’t look up at God and ask why. Derek didn’t do anything wrong. It has nothing to do with that.” He said, “Life doesn’t always go the way you plan it, and the toughest thing for some people is to surrender to the fact that there are things in life that you just have no control over.”

I’m a very lucky guy. I have, including Derek, six children. There wasn’t any time in my life where I could afford to have a substance abuse problem, and I don’t drink, but I have gone with a couple of friends to some AA meetings, and I gotta tell you something. The Serenity Prayer, that’s not a bullshit story. If you live by that, I think that you’d be in good shape because I think a lot of people get hung up where you don’t know the difference between things that you can change and that you can’t. I did everything I could for my son. My wife did, my parents did, the doctors did. The rest of it is in somebody else’s hands. For me to know why, honestly, if an angel came down right now while we are talking and said, “You know what? I heard you talking about your son, and I know you still miss him and you love him, and I’m gonna tell you why he died,” it wouldn’t make any difference. It really wouldn’t.

I just read something the other day, by the way, in front of a dry cleaners in Burbank. They have a marquee at the dry cleaners, and they always have these little quotes up there. And this one said, “Life’s not about surviving the storm, it’s learning to dance in the rain.” That really hit me because that’s really what it is, and to me, when I’m on stage and I make people laugh, I feel like I’m in complete control of everything. It’s probably the only place that I feel in control completely. The minute you step off stage anything can happen, but what’s gonna happen when you’re up there? What – that I bomb and I die? Well, every comic’s died on stage, and one of the first things you learn is there’s life after death. You get to come back to die again. There’s a lot of dying before you start getting funny.

ANDELMAN: Now, Robert, I have to interrupt you there because one of the things that I marked in the book was that you say, “I’m not ready to die period. To begin with, I cannot imagine a future without me in it.”

SCHIMMEL: Yes, because my doctor said, “Here’s what you have to do. Everyday, you have to take a few moments a few times a day, when you wake up, in the afternoon, before you go to sleep, and you have to visualize yourself in the future. You have to constantly do that.” And, to me, I couldn’t see the future without me in it. I couldn’t, and I tried. I really did. I closed my eyes and tried to see my funeral because I wanted to see a lot of people crying and going, “Bob, come back,” and I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. I know the way things go in my life, it just wasn’t gonna be that easy that I would just die and get off the hook. I just wasn’t gonna be gone yet.

Look, I miss my son. I know one day that I’ll be with him, but it’s not time for me to be with him, and I can’t feel bad about it. Did I? Yes. Probably the worst feeling that I had, worse than getting diagnosed with cancer, honestly, was on December 12, 2000 after I finished all my treatment, and I got my first MRI and my CAT Scan, and they said that I was clear and that, starting that day, I can consider myself in remission. And I started suffering from survivor’s guilt because I felt really weird that, “Why did I make it and my son didn’t?”

I talked to my father about it, and my father told me he went through the same thing after the war, that after he met my mom, he said, “Why me? Why did I get to meet the love of my life and have three children and get to see my grandchildren being born, and my mother, father, sister, and brother didn’t?” Well, it’s not for him to know why. There’s no way it could not be funny. When you go to the doctor and he says that you have open sores in your mouth and down your throat cause that’s what happens with chemotherapy, that to avoid any kind of oral/ anal contact, and I’m thinking: Do I look like an ass eater to you? First you tell me I have cancer and now I can’t kiss anybody’s ass? When’s the punishment gonna stop? What did he think I was gonna be doing that? I could barely eat Jell-O.

You’re not supposed to have sex when you’re on chemotherapy because all the chemotherapy in you comes out in all your bodily fluids. So actually they told me that if I had a bathroom that I could use that my wife and daughters didn’t use, that would be the way to do it because guys sometimes pee on the seat, and a girl sits on it, and any that gets on them or in them, that could be dangerous.

And he said, “You could take care of yourself.” Well, it is really hard to lay in bed and pray to God and say, “Please let me get through this,” and then be jerking off in the same bed looking up at the same ceiling. It’s impossible. It just really is. And I prayed, and I had a really hard time doing it, and I’ll tell you why. I think I’m more spiritual than religious. I’m laying in bed asking God to get me through this, and it felt like I had a friend that I hadn’t talked to in 10 years, and out of the blue, I’m calling him and asking him to lend me a thousand dollars. I don’t pray all the time, and then here I am asking for the biggest thing you could ask for, which is not to die, but I prayed to everybody. I prayed to Buddha, I prayed to Jesus, if there had been a G.I. Joe in the room, I would’ve been praying to him, anything and anything to get me through it.

ANDELMAN: You said in the book that the day you were diagnosed, a rabbi came in and then, I guess, priests came in, and you talked about prayer. I think it was the priest who said, “What’s it gonna hurt to try?” I think you also talk about how you’d just as soon talk to all sides because you don’t want to get up there and find out that all those people who were trying to interest you in Jesus that, maybe, they were right.

SCHIMMEL: Yeah. There’s a chaplain in the hospital, and they do their rounds everyday. When the guy came in the first time, he said, “Hi, I’m the chaplain. Are you a Christian?” And I said, “No, I’m Jewish.” He said, “Well, I’m sorry that I bothered you.” I said, “Where you going? I don’t want you to leave.” He said, “Do you want to pray with me?” I said, “Yeah, let’s go.” He said, “Okay, but I’m gonna be praying to Jesus,” and I said, “I’m gonna be right there with you. I don’t want to die and get up there and have Jesus at the gate going, ‘You? Where do you think you’re going?’” Who knows?

I think people invented religion. God didn’t do all that. And so whether you’re Catholic or Lutheran or Protestant or Jewish or whatever, I look at God as like in the middle of a bicycle wheel, and every spoke is a different religion, and it doesn’t make any difference which one you’re on, they all lead to the same thing. As long as you’re on one of them then that’s good.

I did a radio show last week, I think, in New York where I was on the radio with a doctor on the show. And when I said that I prayed when I was getting chemotherapy, he started laughing, and he said, “You really did that?” And I said, “Yeah.” He goes, “You know you’re praying to nothing. There is nothing.” I said, “What?!” And he said, “That’s not real. The Bible is made up by other people. I believe in evolution, and we evolved from apes. That’s where we came from, not from the Garden of Eden and all that stuff.” I said, “Well, if we evolved from apes then why did apes stop having human kids?” And he said, “What?” And I said, “If fish had gills and then they came out of the water and became animals that lived on the land and then they don’t have gills anymore, then if we evolved from apes, how come we stopped evolving?” And there was just dead air space. He did not have an answer, and I thought it was really funny.

I read a book. I read a lot of books when I was going through treatment. I read joke books. I read books on philosophy, on religion. I read a book that was called Searching for God that was written by this rabbi, and I really liked it because the whole premise of it was that he says that when you’re a little child that God is an old man that lives up in the sky with a long beard, and he looks down on everybody, and he sees everyone, he hears everyone, he knows everything, and then when you get older and you’re about the age that you realize there’s no Easter Bunny or Santa Claus that you know there’s no old man that lives up in the sky with a long, white beard. And the problem for most children is most parents don’t have a way to help their kid transition from the old man living up in the sky into the concept of what God or the Creator or whatever you believe it is is. So he says when people say to him I don’t believe in God, he says that’s okay cause I don’t believe in the same God you don’t believe in.

ANDELMAN: I like that.

SCHIMMEL: And you know what? That is the way I was brought up. And I watch George Carlin talk completely in the opposite direction, and it floors me. He makes me laugh so much. I know him. When he came out with the book When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops? or whatever it was, I bought it. I was laughing out loud reading it on an airplane. And the next radio show I did, I talked about how funny his book was, and I get home and he calls me up. And he goes, “Are you plugging my book on the radio?” I said, “Yeah,” and he said, “Why?” I said, “It’s fucking hysterical.” He said, “Schimmel, why would you buy my book? All you have to do is ask me, and I would give it to you.” I said, “I’m not gonna ask you to give me your book. I was on the road, and I wanted to get it then.” Like two hours later, a messenger knocked on my door and handed me this package. I opened it up, and it was the same book from Carlin. He sent it over, and inside it says, Hey, Schimmel, Go fuck yourself – George Carlin.

ANDELMAN: That’s great. That was worth having him send the book over.

SCHIMMEL: Oh yeah. Well, I’ve had some amazing experiences. I was friends with Rodney Dangerfield, and people asked me what he was like, and I say, “Just imagine the movie Back to School or Easy Money and think that Rodney’s not acting. They built a movie around his behavior because that’s the way he really was. There was no ‘Get into the character.’ That was him, and he used to walk around in a jogging suit and a bottle of Evian water, but there was really Absolut Vodka in there and not water.”

I went to go see Rodney in Vegas, and my mom and dad were there. And I wanted my parents to meet Rodney because I thought, You know what? They’re gonna meet Rodney, and they think he’s really funny. They’ve seem him on Ed Sullivan and on The Tonight Show and on the Mike Douglas Show, and they’re gonna really believe that I’m in show business for real

So we go see his show. And my dad’s a real early bird, and he goes to bed like 9:00 at night. So I go up to the dressing room with my mom, and I knock on the door, and Rodney — I swear I am not making this up — Rodney opens the door, he’s wearing a silk robe that has playing cards on it with his balls hanging out, no underwear, literally out of the crack of the robe, he had a joint in one hand and a Miller Lite in the other. And he said, “Hey, you must be Bob’s mom.” I’m like Oh, you’ve gotta be shitting me. This is not what I wanted my mom to see, and he started hitting on my mom. He said, “Where’s your husband?” She said, “Oh, he went to bed.” He goes, “What are you doing later, baby?” He was really something.

ANDELMAN: It’s so nice to hear that, too, because I’ve watched Caddyshack about 200 times, and I wanted him to actually be the guy in Caddyshack because I didn’t want him to be acting.

SCHIMMEL: The first time I met Rodney was perfect. It really was. Talking about things happening at a moment, I had just come off stage at The Comedy Store, and Gallagher came over to me. And comics all hang out back in the out back there of the parking lot and talk and everything, and he was talking to me, and he said, “Where do you think you’re going with talking about jerking off and going to the bathroom? That leads nowhere.” He insulted me in front of other comedians, and right then, Rodney came over to me, and he said, “Hey, kid, I just saw you on stage, and I have a new HBO special I’m shooting next week, and you’re the first person I’m picking to be on it.” And it couldn’t have happened at a better moment. So then Rodney goes, “Hey, you want to have dinner with me?” And I said, “Yeah!” So I go with him to have dinner at the Beverly Hilton Hotel on Wilshire and Santa Monica. We have dinner in there. When we come out, Merv Griffin is standing out front because Merv owned the hotel.

ANDELMAN: Right.

SCHIMMEL: And Merv said, “Hey, Rodney, how you doing?” And Rodney said, “Hey, Merv, everything’s okay, alright?” And as soon as Merv turned around, Rodney went, “Big fag!” and I’m like, Oh, my God. There’s no way that Merv didn’t hear that!

ANDELMAN: Oh my God.

SCHIMMEL: After I finished chemotherapy, Conan O’Brien was really great to me, and he told me, “When you’re done with treatment, whenever you think you’re ready to come on, you let me know, and you’re on.” So I flew to New York. I’m gonna go on Conan. I wanted to even though I didn’t look my best because I had to know for myself that I still had it. I performed in Las Vegas in the middle of chemotherapy because I had to know for myself that even though cancer was ravaging my body the way it was, that it could not touch who I was or my sense of humor or my spirit, and I just refused to give in that way.

I’m walking down Broadway, and Jackie Mason comes out of the Stage Deli, and he’s with two friends, and they’re walking up Broadway. And the two friends stop, and they’re talking to someone else, and Jackie sees me. I’m completely bald. I have a little bit of hair under my lip, no eyebrows, no eyelashes, I’m wearing a baseball hat, and he comes over, and he goes, “Oh, my God, what happened to you?” I said, “I just finished chemotherapy.” And he said, “Chemotherapy? You had cancer? What kind did you have?” I said, “Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma.” He said, “Oh, my God, how you doing now?” I said, “I’m doing okay,” and he goes, “How’s your brother?” I said, “My brother’s great.” And his two friends walk over, and Jackie goes, “I want you to meet a real funny guy, Howie Mandel.” He thought I was Howie!

ANDELMAN: Because you were bald.

SCHIMMEL: And his friend goes, “He doesn’t look like Howie Mandel,” and he goes, “Of course he doesn’t look like Howie Mandel! He just finished chemotherapy. He lost a lot of weight.” And Jackie says to me, “What are you doing in town?” I said, “I’m doing Conan O’Brien tomorrow night.” He goes, “Are you busy tonight?” I said, “No.” He goes, “How’d you like to have dinner, you and me, two intelligent comics, have a nice dinner and a conversation together?” I said okay. He said, “Where are you staying?” I said, “At the Parker Meridien.” He said, “Under what name?” I said, “Robert Schimmel.” He said, “Robert Schimmel? How did you come up with that name?” I said, “That’s my real name.” He said, “Howie Mandel is your stage name?” And he felt so bad for Howie. I didn’t have the balls to tell him I wasn’t him.

ANDELMAN: And did you go through with dinner?

SCHIMMEL: Yeah, and then he winds up telling people that Howie went through chemotherapy. And like a month later, I’m up in Montreal for the comedy festival, and I’m checking into the Delta Hotel, that’s where everybody stays. And the first person I run into in the lobby is Howie, and he comes over to me, and he goes, “So how am I doing?”

ANDELMAN: That’s great. Oh, God.

SCHIMMEL: Yeah.

ANDELMAN: And, of course, everybody talks, so everybody knows.

SCHIMMEL: That’s why I can’t believe the life that I’ve had. When I was a kid, I always loved comedians, and I watched everybody. I’m 58 years old. I remember Sid Caesar and “Your Show of Shows” and Ernie Kovacs and Jackie Gleason and all that stuff, and one of the comics, Jerry Lewis, I idolized, and one of the comics that I really loved that made me laugh so much was Jackie Vernon, and I got to work with him a couple of times.

Once they called and said, “Hey, this guy’s opening. Do you think you want to go work at this place?” They don’t tell me who it is. I get there, and it says, “Tonight Only, Jackie Vernon.” And I’m like, “Holy shit!” and I’m hanging out with him. And then he goes, “You’re pretty funny. I’m doing this gig at the Hoosier Dome. You want to do that with me? It pays a thousand dollars for the opening act for one night in a first-class arena. You sign for meals.” I said okay. Well, we get there, and it’s a religious convention, and Jackie was completely clean. It was nothing you could find offensive in anything he said no matter who you were. He could literally do a show in front of the Pope. There was nothing. And these guys that were like the Oddfellows or whatever they’re called, they looked like Amish people, but they’re not Amish, but it’s almost something like that. So we get there, and he goes, “Oh, boy. This isn’t gonna be good. Let me tell you how we’re gonna do this. I’m gonna go on first because they know me, and I’m gonna go do the show. Then I’m gonna bring you on and introduce you as my protégé, and as soon as I get the check, I’m gonna give you the signal, and you say, ‘Good night.’” I said okay. He goes on, does 45 minutes, they love him, and then he goes, “Now I’d like to bring up this young, up-and-coming comic. He’s a really funny guy. He travels with me on the road. Robert Schimmel!” and I walk out there. He hands me the mike, and I said, “So I’m taking a shit…” and he grabbed the mike out of my hand, and he said, “How about another hand for Robert Schimmel, ladies and gentlemen?” And I turned to him, and I said, “What about the signal?” And he said, “We’re waaaay past the signal.”

ANDELMAN: One of the things I wanted to ask you about was who makes you laugh now, but you mention Jackie Vernon, and I’m thinking, Great comic, but Jackie Vernon makes Robert Schimmel laugh? Who would’ve guessed?

SCHIMMEL: A lot of people make me laugh. There’s a lot of guys on the road that I work with that people never hear about. Chappelle makes me laugh, Dennis Miller makes me laugh, and Sarah Silverman makes me…There’s a lot of people. I love to laugh. I just really do. And one of the biggest things for me, as far as in my comedy career, is my manager called me about a year and a half ago, and he goes, “Did you read The New Yorker magazine this week?” And I said no. He goes, “There’s an interview with Jerry Lewis in there, and they asked him who his favorite comics were, and he said you and Richard Lewis.”

ANDELMAN: Wow!

SCHIMMEL: I’m like, “What?” So he said, “You should call him up and thank him.” I said, “I’m not gonna call Jerry Lewis!” I was in love with this guy. You can’t tell by my act, but I used to emulate him as a kid. I would knock stuff over intentionally. I wanted to be him so badly. I even wore white socks with a suit. And I said, “I can’t call Jerry Lewis up. I can’t. Rodney you can call, but Jerry Lewis, that’s another level completely.” He said, “Well, at least call his office and just leave a message for him.” So I call up, I leave a message for him, and I said, “I just wanted to please tell Mr. Lewis that I read the thing in The New Yorker and that I really appreciate it.” I go to lunch with my wife, and my cell phone rings like a half an hour later. And I go, “Hello?” and it’s Jerry Lewis. I’m like what? He goes, “What can I do for you, kid?” And I couldn’t talk. I really couldn’t talk. And he goes, “I don’t like the phone. What are you doing tomorrow?” And I said, “Nothing.” He goes, “Why don’t you fly up to Vegas? We’ll have someone pick you up at the airport, and we’ll hang out tomorrow.” I almost started crying. You have no idea. This is why I can’t not be positive about life, okay, because I’ll tell you how wild it is in this world and this business. I would’ve never, ever dreamt in my wildest imagination that Jerry Lewis would ever know who I was, ever, before I was in comedy and even when I was in comedy. And I know for a fact that he does not go for profanity at all. It’s something that he detests. He doesn’t like it.

And I go up there. He said, “I saw your HBO special. I was in the hospital. I gotta tell you, kid, I almost started crying. You made me laugh so hard.” And I sat there, and I couldn’t talk, and he said, “You don’t want to talk to me?” I said, ”I can’t. I can’t believe I’m with you.” He said, “You’ll get over it.” And I was there like all day. The night before, I didn’t go to sleep. I literally was like a girl, asking my wife, “Should I wear these pants and this shirt?” I was getting to meet my idol.

ANDELMAN: Right.

SCHIMMEL: And then he was so nice to me. I spent the whole afternoon, and I gotta tell you. You hear these stories about people, Streisand and Jerry Lewis and these other people that are supposed to be real assholes and everything. Well, I don’t think they’re assholes. I think that they’re maybe perfectionists and that it’s their career, it’s their name, people are coming to see them, and they just want the shit to be right. It’s not being an asshole if you want it to be right, and he told me that. He goes, “I would love to tell you that Dean and I were geniuses and that we had the whole thing planned out, but it wasn’t. We were really lucky. We were two guys at a time. The timing was perfect. It was right after the war, and people really loved the camaraderie between Dean and I, and we were getting $50,000 a week in the fifties.” In the fifties, they were getting $50,000 a week, and he said, “Our best jokes would be throw-away lines for real comedians who are getting $50 a week.” And he told me that he missed Dean every day and that he talked to him everyday from the day Dean’s son died in a plane crash, and he said, “It’s not true that we never talked to each other. It’s just that I couldn’t go anywhere without them asking where Dean was, and Dean couldn’t go to a party without them saying, ‘Where’s Jerry?’” and that they had to know who their own identity was for themselves and that he wanted to be a director. He liked staying on the set and doing all that stuff, and Dean would want to do his thing and go play golf. He said it wasn’t that they hated each other and was a big blowout thing, that they decided to end while they were on top because he said they knew it could only last so long and that they didn’t want to split up on the way down.

ANDELMAN: Robert, you mention Jerry Lewis, which is interesting to me, because as I was reading the book, I was actually thinking a little about him because one of the things that happens in the book is that you, and just by virtue of publishing the book I’m sure this is the case, sharing your story and talking about it, in some ways, you are kind of helping people. And I was actually thinking about Jerry Lewis. I can’t really make a neat, clean parallel here, but here’s a guy who was affected by something at some point and just really changed the tenor of his career.

SCHIMMEL: I know, but he won’t talk about it. When I was with him that day, he said, “You can ask me anything you want except why I do the Muscular Dystrophy Telethon. That’s a personal thing, and that is gonna go to the grave with me, but you can ask me anything else.” And people can make fun of him and say that’s a real hacky thing and that it’s all a put-on the way he acts. Well, I spent a day with him, and I don’t know what it is. Something definitely happened that he’s that passionate about it, but you can say whatever you want about him, but there isn’t anybody else raising that kind of money for Muscular Dystrophy. How can you knock him for doing that? Talk to people, parents, that have kids that have it, and they’re not gonna say he’s a hack. Where would they be without him? God knows how much money he’s raised since he started. It’s a lot. So I don’t think it’s selling out doing stuff like that.

That selling out thing with comedians is a really bizarre deal. You do network television, and then people go, “He sold out.” Well, that’s just like saying that people say you’re a “Comedian’s comedian.” That’s great, but being a comedian’s comedian doesn’t pay a lot. Comics don’t pay to see other comics. You get in for free. And for you to not do “The Tonight Show” or Letterman because you want to show people that you’re not gonna do that kind of thing, well, not only is it shorting yourself, but don’t you think even if you were me or Sam Kinison or Bill Hicks or Richard Pryor or whatever, that if you did Letterman or “The Tonight Show” or Conan, that all your fans would say, “Wow, he’s on ‘The Tonight Show’? I knew this guy was funny 20 years ago.” Nobody’s gonna say we don’t like you anymore because you did network television.

ANDELMAN: You were on Howard Stern last week so he teased you by saying that you were finally going on “The Today Show” but only because you got cancer. Lots of people knew you were funny, but it took that to get you on there. How did that go, and what did you think about that?

SCHIMMEL: First of all, that was the wildest radio show I was ever on. My wife has absolutely no desire to be in show business. She did not go there to be on Howard. She’s never been on Howard. My daughter’s been on with me a few times and that was only because once, the first time I went and my daughter went with me, she was in the Green Room, and Gary went and got her and brought her in. That was the first time I ever saw Howard back down was with my daughter because he said, “Wow, you’re a really cute girl,” and she said, “Oh, thank you.” And Howard said, “How’d you like to model a couple of bikinis for me?” My daughter said, “Sure. Bring your daughter in, and we can do it together,” and he changed the subject immediately.

The first time I did Howard I had no idea what to expect. My CD had just come out on Warner Brothers, and the president of Warner Brothers was friends with Howard, and Howard’s soundtrack for his movie was on Warner Brothers. He sent Howard my CD. He thought it was funny. I go there, they bring me in, I sit on the couch, he goes, “Here’s a real funny guy, Bob Schimmel. He’s a new comedian.” Howard is the only one that calls me “Bob.” As he goes, “Bob Schimmel, and he’s got a really funny CD out,” I sit on the couch, and he goes, “You had a kid that died, huh?” That was the first thing he said, and I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “Wow, that must’ve been really something, huh?” And I’m like, Geez, where’s he going with this? So I said, “Howard, yeah, I did have a son. His name was Derrick, and he passed away in 1992. And I gotta tell you that, when Children’s Hospital sent him home and said they couldn’t do anything anymore, the Make-a-Wish Foundation came to our house, and this is a true story. They said, ‘We’d like to make a wish come true for your son,’ and I said, ‘Well, his wish is to watch Dolly Parton blow me.’” And Howard screamed. They cut to a commercial, and Gary Dell’Abate came over to me and said, “You can be on for the rest of your life.” I said, “Why?” And he goes, “Because that was unreal. There is no way that Howard expected that kind of comeback. You could’ve made him look like a real creep at that moment, and instead, you came up with the line that got him.” What Howard originally got famous for was getting the best out of people where they wouldn’t do it on any other show. And he was really great.

Howard used to call me when I was in the hospital. He actually called me once, and I was live on the air, and I didn’t know. I felt really shitty. It was like after my sixth chemotherapy, and I’m really just beat up badly. I’m laying in bed, and the phone rings, and he goes, “Hey, Bob, it’s Howard.” And I said, “Hey, Howard, how you doing?” He goes, “Can I ask you a question? Do you think you’re gonna make it to New Year’s Eve?”

ANDELMAN: Oh, I remember that.

SCHIMMEL: I said, “What?!” And he said, “… because Robin’s got Anthony Quinn in the death pool, and I don’t know whether to pick him or you.” I said, “Are you shitting me?” And he said, “Hey, watch your mouth, we’re on the radio!” And I’m like, ”We’re on the radio? You’re calling me, and you don’t tell me? You know what? Go with Anthony Quinn because I’m not dying.” Then Anthony Quinn fucking dies! I can’t believe it. This guy wasn’t even sick. He had a kid when he was 75 years old or something. He dies, and Howard said, “I picked the right person.” I’m like, “Oh, man, I feel really shitty that that happened.” I just really did.

It’s amazing to be in this. I loved making people laugh ever since I was a kid. I didn’t know I was gonna be a comic. I don’t know if you know, but I got into this business totally by, I was tricked into it, basically.

ANDELMAN: I didn’t know that.

SCHIMMEL: I was married already to my first wife, living in Scottsdale, Arizona. I grew up in New York. I had Jessica, my daughter who was on Stern last week, and I was managing a high-end stereo/video store in Scottsdale, Arizona. It’s called Jerry’s Audio, and it was great. I was having a great life. We had a brand new house we lived in. I went to visit my sister in L.A. It was just me; my wife and daughter didn’t come. On Saturday night, she took me to The Improv on Melrose, and even though I watch comics all the time on TV, I had never been to a comedy club. This is 1980 before the boom, and there weren’t clubs everywhere, and she signs me up on this amateur thing. And the way it works is you put your name on a piece of paper, you fold it up, you put it in the wastepaper basket. Bud Friedman, the owner of The Improv, actually was the emcee of the show. He would stick his hand in the bucket, pull out a piece of paper, read the name, and you got two minutes on stage. He had an egg timer on the bar stool on stage, and they would set it for two minutes, and when the timer went Ding!, you had to say, “Good night,” even if you were in the middle of a joke and you couldn’t get to the punchline. “Good night,” and that’s it. Well, my sister signs me up without telling me, and I’m sitting in the audience, and I’m having a beer with her, and all of a sudden, he goes, “Robert Schimmel!” And I’m like, What? She goes, “Come on, you’re funny. Get up there!” And I said, “I can’t get up there!” and Bud’s like, “Come on, don’t chicken out. Where are you? Don’t we want him to get up here?” And the crowd is clapping. So I go up, and I said, “I’m not really a comedian, I’m a stereo salesman, and my sister signed me up because she thinks I’m funny, and I don’t know anything about show business. I could sell you speakers…” and they started laughing! I said, “Please don’t laugh, because everybody has a sexual fetish or a fantasy, and mine is to be humiliated in public in front of a lot of people.” And somebody yelled out, “Go fuck yourself!” and I said, “Thank you very much.” They started laughing. I got off. Bud came over to me, and he said, “Sign up for spots. You can work here whenever you want.”

ANDELMAN: Wow!

SCHIMMEL: And that’s all I needed to hear. That two minutes on stage hooked me right away, and I go back home, tell my wife I want to be a comedian, put the house up for sale, quit my job, pack everything up in a U-Haul. “We’re gonna drive to L.A., we’re gonna crash at my sister’s until we find an apartment, and I’m gonna be a comedian.” Well, we drive to L.A., I get off the Hollywood Freeway on the Melrose exit because I want to show my wife the club that I’m gonna be performing at, and it burnt down the night before we got there.

ANDELMAN: And was this the first divorce or the second divorce?

SCHIMMEL: No, this is the first.

ANDELMAN: Okay.

SCHIMMEL: And it was still smoldering.

ANDELMAN: Wow!

SCHIMMEL: The sidewalk and the street were still wet, the windows are boarded up, there was this smoky steam coming out of there, and Bud was out in the street talking to insurance guys and whatever. And my wife said, “Oh, my God!” and I said, “Don’t worry; I’m sure they have insurance.” She said, ”Who gives a shit about them? You sold the house, you quit your job, and now the place doesn’t even exist!” I walked over to Bud, and I said, “Wow, what happened?” And he said, “Do I know you?” And I’m like, You gotta be kidding me! He didn’t even remember who I was anymore, and that was it.

I got a day job selling stereo equipment in Beverly Hills, and I wound up — this is such a crazy life — I wound up selling a stereo to Steve Martin. And I go to his house to install it, and I’m in Steve Martin’s house, and I’m on my hands and knees. I’m laying speaker wire, running it under the rug from the living room into the den and this other room, and he’s there. He’s home while I’m doing it, and he comes into the room because I was working at the stereo store in the daytime and then getting on stage on amateur nights at the Comedy Store and the Laugh Factory and Osco’s Disco and any place where they had a comedy night. And I said, “I’m a comedian, too,” and Steve said, “Yeah, that’s why you’re installing my stereo system.” And then I’m like, Oh, God, I sound like Rupert Pupkin. I wind up getting discovered by William McEuen, and he’s the guy that discovered Steve Martin. If you look at all Steve Martin’s albums, they say, “William E. McEuen presents Steve Martin.” That’s what it says on mine: “William E. McEuen presents Robert Schimmel.” On my second CD, Steve Martin wrote the liner notes.

Robert Schimmel Wikipedia • IMDB • New York Times obituary • Order Cancer on $5 a Day via Amazon.com

LISTEN! Robert Schimmel returns to Mr. Media (April 4, 2008)

WATCH! Geri Jewell interview with Mr. Media about her friend and roommate Robert Schimmel

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!