Trina Robbins, the author of the GoGirl! series of comics from Dark Horse, joins us today as our guest.

Trina Robbins Website • Blog • Facebook • Wikipedia • Trina Robbins 2009 interview with Mr. Media

BOB ANDELMAN/Mr. MEDIA: Trina, is the pre-teen and the teen girl, is that a new reader of comics? I just don’t remember any girls when I was that age being interested in comics.

TRINA ROBBINS: Well, you don’t remember because you are not old enough, but no, it is not a new reader of comics. There used to be tons of comics for pre-teens and teen girls all through the 1940s and ’50s and well into at least the middle to late ’60s, and then they all disappeared in favor of superheroes, which girls basically are not interested in. The average girl is not interested in superheroes, so suddenly, girls weren’t reading comics any more because there were no comics they wanted to read.

ANDELMAN: What were they reading in the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s? What were some titles?

ROBBINS: They were reading comics about teenagers, usually about teenage girls, although they read Archie. You talk to a lot of women of a certain age and ask them what they read when they were a kid, and they read Archie comics, but they won’t call it that, they’ll say, “I read Betty & Veronica,” because that’s who they related to. And there were other titles. Stan Lee, the editor of Marvel who has given us Spider-man and The X-Men and the Fantastic Four in the ’60s gave us so many teen titles in the ‘40s. The biggest two were Patsy Walker, which was about a teenage girl, and Millie the Model, which lasted a long time. You’ll find a lot of people who remember Millie the Model because it lasted through the mid-’70s. Archie Comics also gave us Katy Keene, who was a model, and the girls just loved Katy Keene and used to send in drawings and designs for her clothes, and again, you find women past a certain age, and they’ll all tell you they loved Katy Keene when they were little girls.

ANDELMAN: And didn’t Marvel eventually bring Patsy Walker back, but like as a superhero or something?

ROBBINS: No. The less said about that, the better.

ANDELMAN: I am actually old enough to remember the comics in the ’60s that you are talking about. There were those things, and there was another one I remember. I guess it was into the early ’70s. There was a Marvel comic, I think Night Nurse or something like that.

ROBBINS: Oh, Night Nurse! Yes, that was part of kind of their desperate attempt to regain the girl audience, but at that point, it was too little too late.

ANDELMAN: Why has it taken thirty years for comics publishers to rediscover women? Does it have something to do with the Japanese influence?

ROBBINS: It has everything to do with the Japanese influence.

Up until Manga arrived on our shores, American comic editors and publishers suffered from a kind of collective amnesia and used to say, well, girls don’t read comics. I mean, I have some unbelievable quotes from them. They actually said, “Girls’ brains are wired in a different way, so they just don’t get comics.” Somehow, it never, ever, occurred to them that girls weren’t reading comics because girls are not interested in overly muscled guys with square jaws punching each other out.

Somehow, they just didn’t see that at all, they just saw girls don’t read comics. But now we have all these incredible Manga, Shojo Manga, which is the Japanese term for girls Manga, and the girls are eating them up. You go into any chain bookstore like Borders or Barnes and Noble, you go to the graphic novel section, you see these teenage and pre-teen girls sitting on the floor surrounded by Manga, reading them.

ANDELMAN: I did not know that that’s what Shojo meant. See, I’ve learned something already today.

ROBBINS: And the boys’ are called Shonen Manga. And there is definitely crossover. Girls read Shonen and boys read Shoujo.

ANDELMAN: I feel like a giant light bulb just went on over my head now that I understand that. It’s the generation I’m in, I guess. I never stopped to understand what those two meant.

ROBBINS: Now you know!

ANDELMAN: I feel greatly enlightened. Now, let’s talk about GoGirl, which I mentioned before we actually started the interview that my daughter really, really enjoyed. For those who may be scratching their head who don’t know GoGirl like they know Betty and Veronica, could you tell us a little bit about who GoGirl is and a little about the adventures?

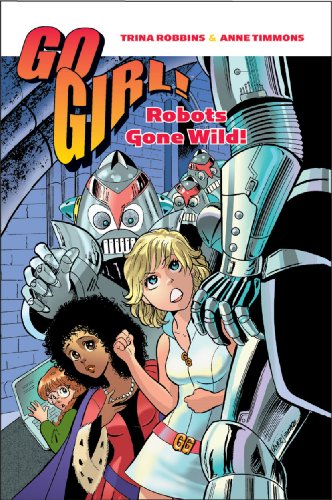

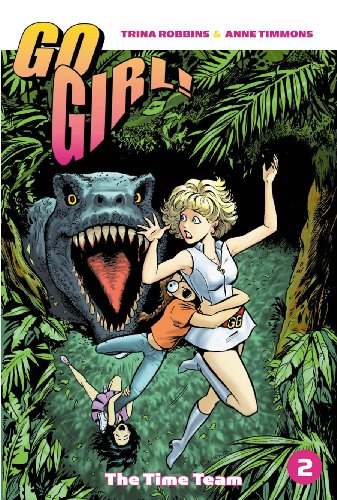

ROBBINS: Sure. I’ll start by saying that it’s published by Dark Horse so you can know where to look for it. GoGirl is a fifteen-year-old girl whose mother was a super heroine, and her mother’s name was GoGoGirl, and she wore a little white go-go mini-dress and white go-go boots, and she could fly. Then she stopped. She got divorced. She had to be a single mother and support her daughter. She had stopped even before that, because her husband felt threatened by being married to a woman who could fly, which will tell you why the marriage didn’t last. But anyway, she doesn’t know, in the beginning, anyway, she didn’t know that her daughter had inherited her ability to fly and was flying in secret because she kind of knew that her mother had bad feelings about it. Then our heroine had to put on her mom’s old costume, which fit her perfectly, and go out and rescue her best friend when her friend got kidnapped, and that was when the world finally learned that they had another super heroine, a flying girl. And her mother has been very supportive and sometimes jumps in on the action wearing the extra outfit because she had to have two costumes so that when one was at the cleaner’s, she could wear the other. But that’s all she can do. That’s all she can do; she can fly. Otherwise, she is a perfectly normal teenage girl. She doesn’t have X-ray vision, she doesn’t have fists of steel, she can fly.

ANDELMAN: And Trina, which parts of this are autobiographical?

ROBBINS: None, except for the fact, of course, that I’m a mother, and I have a daughter, and I love my daughter. And we have a good relationship as do GoGirl and her mother.

ANDELMAN: I see. All right, so there’s no flying going on in your house?

ROBBINS: Oh, how I wish.

ANDELMAN: Why did you start this series? Is it because there was all this Japanese Manga that was going on, or did you…

ROBBINS: No. We did this pre-Manga. This goes back to 1999. Anne Timmons is the artist, by the way, and she is just such a fabulous artist, and we work together as a writer/artist team so well that I have called us the Stan Lee and Jack Kirby of girls’ comics. We first met at a convention in the late ’90s and kind of became email pen pals, and then one day, she said, “Let’s do a comic together. You write, and I draw.” And I thought, “Fat chance we’ll have of selling this,” because in those days, Manga had not really gotten its hold on the United States yet, and there was really very little out there for girls, but I thought, what do I have to lose? I have a file cabinet in my head of all these comics ideas that I want to do, and I pulled out of the file cabinet the file on the flying teenager and created GoGirl! In the beginning, Image was publishing us in comic book form, but you may or may not know that the problem of comic books if you’re aimed at girls, not so much any more, because of Manga, but in those days, if you were aiming your comic book at girls, you had a terrible time getting it distributed. There were comic book stores that simply didn’t want to carry girls’ comics, and all they had was superhero comics for boys.

ANDELMAN: Well, they probably didn’t see many girls in their stores, so why would they think to carry them?

ROBBINS: Well, you see, it’s this vicious cycle. The girls didn’t go in the stores because there was nothing there for them. Plus, the stores were wall-to-wall teenage boys, which is very intimidating if you are a young girl. So, of course, the girls didn’t go into stores. So then everybody could say, “Oh, girls don’t read comics,” right? But anyway, we had five issues of the comic book, and then we went over to Dark Horse, and Dark Horse published the first five issues as a collection, a graphic novel collection, and it was about that time that Manga started hitting, especially Shojo Manga started hitting. Girls who had been starved for comics for twenty years finally found comics they liked, and we could get graphic novels in bookstores, so we have since then done two more graphic novels, and we hope to produce another one next year.

ANDELMAN: Trina — and I say this with all due respect — you have been around comics for quite a while now…

ROBBINS: Too long.

ANDELMAN: How did you get interested in the field?

ROBBINS:

I’m one of those people who’s old enough to have read those comics when she was a kid. I read Millie the Model, and I read Katy Keene, and I loved them, and so then when I grew up and I heard all these editors saying, “Girls don’t read comics,” I knew it wasn’t true.

Simple as that, I knew it wasn’t true because I had read them, and my girlfriends had read them, and we used to read them and trade comics, just like kids do today.

ANDELMAN: But I mean, what would make you think, since there were not many women in the field, because you’ve done cartoons, you’ve done comics, you’ve done histories, I can’t imagine it was a very welcoming field as a professional.

ROBBINS: No. Absolutely not, and that was a shock, because it had somehow never occurred to me that comics was a boys’ club. I mean, it didn’t occur to me that people would think, “Oh, you are a girl, you can’t do comics,” and so it was really a shock when I discovered that. But by then, this other thing had kicked in, which is the “I’ll show them” syndrome.

ANDELMAN: Were there any women that did mentor you at all or that encouraged you that were in the field?

ROBBINS: Well, actually, when I saw my first underground comic in 1966 in a New York underground newspaper called The East Village Other, it was this very, very psychedelic full-page comic called “Gentle Trip Out,” and it was signed “Panzica.” I had no idea who Panzica was, but I looked at it, and I said, I want to do this. Not literally that comic, but I want to do comics, and two years later, at that point, I was living in New York, and I was contributing comics to the East Village Other, I found out that Panzica was a woman, so you could say that my first inspiration was a woman, and I didn’t even know it.

ANDELMAN: I’m glad you mentioned the East Village Other, which this will be the second time it’s mentioned in Mr. Media. What other kinds of things did you do in the ’70s, because you’ve had a very diverse career, I know?

ROBBINS: Well, I did lots of comics, because I still had that ‘I’ll show them’ syndrome. I did lots of comics. Actually in 1970, I produced the first all-woman comic book ever that was called It Ain’t Me, Babe, and it was named from the feminist newspaper I was working on, It Ain’t Me, Babe. Actually, in those days, we called it “Women’s Liberation.” It was the first women’s liberation newspaper on the west coast, and I was kind of the unofficial artist and art director, but everybody was very egalitarian, so we didn’t have titles.

ANDELMAN: It’s hard to believe that that term has in some ways become an antique. You don’t hear it very much any more.

ROBBINS: Women’s liberation?

ANDELMAN: Yeah.

ROBBINS: Of course not. It really dates you, doesn’t it?

ANDELMAN: Yeah, it really does.

ROBBINS: If some old guy says, oh, yes, I’m on the side of you women’s libbers, you know how old he is.

ANDELMAN: Oh you know, I’m hearing you say that, and I’m thinking of Archie Bunker making cracks about it.

ROBBINS: Exactly. He used to use that term, didn’t he?

ANDELMAN: Oh yeah, and kind of the way Rush Limbaugh would refer to….

ROBBINS: Feminazis.

ANDELMAN: Feminazis, thank you. Yeah. Generation apart, but same basic attitude. So were there any women over the years that helped you or that mentored you along?

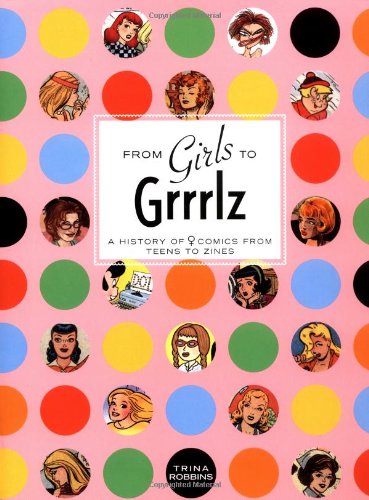

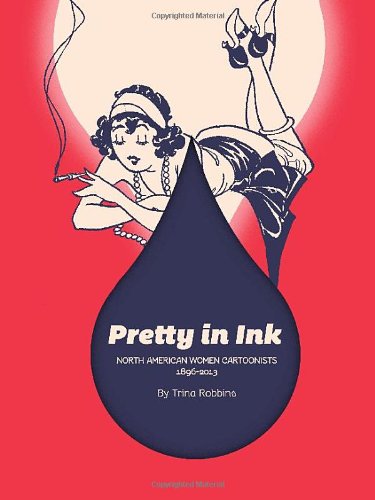

ROBBINS: Not really. There weren’t any around to help me or mentor me, but I’ve been inspired by a lot of early women cartoonists whose work I’ve researched and whose stories I’ve looked up and researched. I’ve just been inspired by what they did. I’ve published really three books on women who worked in comics, two of them simply on the history of women cartoonists. Because the other thing that all those editors used to say besides “Girls don’t read comics,” is they used to say, “Women have never written or drawn comics.” Again, I knew this wasn’t true. So I researched, and I found hundreds of women over the 20th century who had done comics.

Back in the very early days of the 20th century, there were lots of women drawing comics for the newspapers, and nobody thought it was unusual.

They didn’t have to take male names, contrary to strange public belief that women had to take male names to get published. It wasn’t true, and nobody said, “Oh, this is weird. You can’t do a comic because you’re a woman.”

ANDELMAN: Let’s mention some of these titles, because I’m aware that you did A Century of Women Cartoonists, and what was the other history?

ROBBINS: Yes. The Great Women Cartoonists.

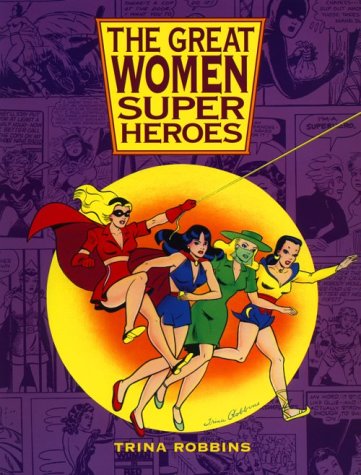

ANDELMAN: And I know you also did a book, The Great Women Superheroes.

ROBBINS: Yes.

ANDELMAN: Who are some of these women? Let’s go ahead and mention some names.

ROBBINS: Well, we could start with the very, very early earliest. The earliest comic I found was from 1896, and that was drawn by Rose O’Neill, who became famous as the creator of the Kewpies, and she did Kewpie Comics. She was also an artist and a magazine illustrator, a very, very good artist.

ANDELMAN: Kewpie Comics I know about, having done Will Eisner’s biography. He published that, and he thought that was going to be so huge, and it was one of his great disappointments was that it didn’t fly for him, but I know exactly what you’re talking of.

ROBBINS: But you know, you can still get Kewpie products, and there are still lots of Kewpie fans who have conventions every year.

Another one was Grace Drayton, who was incredibly prolific. We’re talking about really early 20th Century, like she started in 1903, okay, and in 1906, she created the Campbell’s Soup Kids. She drew comics about little kids, and they all looked like that. They were all these roly-poly little kids with little round noses. She did so many, about 10 or 12 titles, really. She was amazingly prolific in American newspapers everywhere.

A little later, well, actually starting in 1907 but very popular in the teens and ‘20s was Nell Brinkley, who was famous for these beautiful, beautiful women she drew, and they were called the Brinkley Girls. They’re just breathtakingly beautiful. When I show her work in slide shows, people just gasp. She was so successful that she was a household name. Newspapers used to write articles about her. You could buy products; you could buy Nell Brinkley hair curlers. The women she drew used to have this wonderful curly hair. I guess the idea was, if you bought these hair curlers, you could have hair like that, too. The Ziegfeld Follies had an act called the Brinkley Girls in which the showgirls in the Ziegfeld Follies in the early 20th century would be all in white, and then they would be outlined in black. Their clothing would be outlined in black so that they looked like moving drawings.

Let’s see, who else? Okay, we get into the twenties, Ethel Hayes, again, was a really, really prolific cartoonist who also drew flapper comics, really cute little art nouveau women kind of inspired by John Hill, Jr., and again, she did everything. She illustrated children’s book. If you Google her, you’ll find so many children’s books that she illustrated. She was really great.

ANDELMAN: And then, Trina, if we come forward, now today, I know you’re not the only one working in the field. Who are some of the…..

ROBBINS: Oh, there are more women drawing comics now than every before, ever.

ANDELMAN: Who are some of the creators today, female creators, and what are some of their projects?

ROBBINS: Well, let’s see, immediately what comes to mind is Roberta Gregory, who does a comic called Naughty Bits about a woman named “Bitchy Bitch,” who is just as you would imagine she would be. It’s uproariously funny. Roberta has been around for quite a while doing this comic. Let’s see. Jessica Abel, who just came out with a wonderful graphic novel called La Perdida. Leela Corman, who has done a graphic novel and is about to have another one come out, is a very, very good artist. I really like her stuff. Suddenly, I draw blanks when I have to think of contemporary women, but there are so many. There are really more than ever before.

ANDELMAN: There’s actually an organization now, right, too?

ROBBINS: Friends of Lulu.

ANDELMAN: Friends of Lulu.

ROBBINS: Friends of Lulu started in 1994 when nothing was more needed than an organization to inspire women and to encourage women, because, really, women were just about invisible in comics in 1994. Things have gotten much better, but it’s still really, really helpful to have a group like this. Friends of Lulu is a non-profit international organization. We have members in Canada; some people in Europe get our newsletter. It’s dedicated to encouraging participation in comics for women both as creators and as readers, so that they’re pushing women-friendly comics just as much as they’re pushing women comic creators. And I cannot recommend it enough for women who want to draw comics or who want to know what they should be reading or what they should be looking for if they want to read comics.

ANDELMAN: It shouldn’t surprise anyone who’s gotten this far with us in the conversation that a woman who is that interested in the history of women and cartoonists has actually worked on a series also about women. You did most recently Hedy Lamar and a Secret Communication System for Capstone, and it was very interesting to me to see that. I remember, it seems like it must be almost eight to ten years ago that there was a cover story in Scientific American that got a lot of attention about Hedy Lamar having worked on this anti-torpedo system, and people were like, what?

ROBBINS: That’s right. It was a radio-controlled torpedo system.

ANDELMAN: But what made you look at that, and I don’t know if it was your idea or if someone brought the idea to you to do this.

ROBBINS: Well, I was very lucky. The publisher of Capstone, you probably noticed I did four different women for them. They published these educational graphic novels for kids, and they gave me my choice of women to do. Besides Hedy Lamar, I did Elizabeth Blackwell, who was the first woman doctor. Florence Nightingale, who made the nursing profession respectable, because before that, it was not respectable at all, who did so much for nursing. Bessie Coleman. I am really proud of that one. It’s gorgeously illustrated. Bessie Coleman was the first African-American woman to get her pilot’s license back in 1921. And since they gave me a choice of subjects, when I saw Hedy Lamar, I just snapped it up, because I knew a little about Hedy Lamar. I knew she had been an inventor, but of course, researching this, I found out so much more about her, and her story is just amazing. Not just that this woman who was called the most beautiful girl in the world, and she was really was so beautiful, this actress. Not just that she was so smart and she had created this invention. But her daring escape from Austria in 1937 is just the stuff of movies itself. I’m waiting for someone to do a movie about it. She was this teenager — she was just 17 when she made her first movie, and she was this gorgeous Austrian actress, and she was married to this rich man. She was his trophy wife, and he was a terrible person. He was selling arms to Hitler and Mussolini, and she hated the Nazis, and she hated him. But he had her closely guarded so that she couldn’t get away. He had people following her every move, so even though she lived in the lap of luxury, she was like a prisoner in her own home. She hired a maid who was roughly her size and had hair like hers, and she drugged the maid with three sleeping pills in a cup of coffee and changed clothes, changed into the maid’s uniform and made her getaway and left Austria, and eventually, she toured. She was on the stage in England. Eventually, on the ship to America, Louis B. Mayer was on the ship, and she signed a contract with him right there on the ship to become an American movie star.

ANDELMAN: And one of the most interesting parts of her story, of course, is later, she’s so frustrated with the Nazis, she finds someone, and she’s talking to them about radio-controlled torpedo systems. And they’re like, well, how do you know about this? Well, my husband doesn’t know, but I was listening very carefully when he was involved in this.

ROBBINS: Everyone thought that just because she was beautiful, she was stupid.

ANDELMAN: Right. It was a great story, and this was another one. My daughter read that this week, too, and just was like real interested, and you know, you can just see, you can see the little light going on in the little girl’s eyes and the head going, wow, when they say I can do anything, I can really do anything. I mean, I assume that’s part of what you’re getting at with these books.

ROBBINS: That’s what I hope. That is exactly the result that I hoped for in these books that I wrote. Yes.

ANDELMAN: It works. I think the more kids, the girls, especially, that have access to this…. I’ve been stocking my daughter’s shelf for when she’s a little older. Any time I see something about women accomplishing things and getting recognized for it, I’ll just slip something up into her shelf up in the top of the closet, and eventually, she’ll be old enough to, “What is that stuff up there?” And climb up and take a peek. Are there more books coming in that series?

ROBBINS: Not at the moment, but they have kind of an offshoot publication called Stone Arch that is doing books that are not specifically aimed for classrooms that will be sold in bookstores. I know that these are sold on Amazon.com. I’m not sure about the bookstores, but they are doing books that are going to be sold in bookstores, children’s graphic novels, and I wrote something for them. I really can’t tell you when it’s going to come out, because it’s in production, but I’m very proud of it, and it’s about a 14-year-old slave girl who escapes from slavery via the underground railroad, and I’m really proud of this book. I can’t wait to see the finished product.

ANDELMAN: Does it have a title yet?

ROBBINS: Well, I’m calling it “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” and I’m not sure yet if they’ve decided to keep that title or not.

ANDELMAN: Okay. Now, you and I are an easy sell on comics. Obviously, we both grew up on them, reading them, and believe in their value, both entertainment and clearly these days, with your work, educational. But not everyone believes that comics are the best format to teach children anything and, to be honest, that includes my wife. It’s an issue in my own house. How do you respond to people who are still dubious about the genre after all these years?

ROBBINS: Well, you know, that’s changing a lot. I contributed a chapter to a book on graphic novels aimed at librarians. My chapter, of course, was on graphic novels for girls. Librarians and teachers and school librarians, also, are discovering that even if kids won’t read books, they are likely to read comics, and you can produce literate comics for them. I’m very proud to say that all of my comics are very literate, that the spelling is always checked, because yes, it is true that there are comics that are pretty illiterate that are just a bunch of fight scenes. But more and more people are aware of the fact that this is a way to get kids to read. And if they read enough comics, they may decide to read a book. For Scholastic, back in the year 2000, I think, I turned a bunch of classic novels into graphic novels. I took something like, believe it or not, Hamlet, and turned it into a twenty-four-page graphic novel. I took The Odyssey and turned it into a graphic novel. I did the same thing with David Copperfield and with Jane Austin’s Emma, and the idea is that if these kids read the graphic novel and they like it that they might some day decide to read the book itself, and I’ve gotten fan mail from kids about these books. It’s really cute.

ANDELMAN: Now, before we wrap up, I wondered if you could make a case for encouraging other women to follow you into the comics field?

ROBBINS: You know, I don’t think I even have to encourage anyone any more. You know, more women than ever before are creating comics, and it’s all around you. You don’t need like the one person to say, oh, come join me, do comics. I’m surrounded in the United States by women who do comics.

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!