Today’s Guest: Larry Ratso Sloman, author or co-author of celebrity memoirs from Howard Stern, Abbie Hoffman, Anthony Kiedis, Phil Esposito, Mike Tyson, and a biography of Harry Houdini

Writing the biography of a well-known person in pop culture is an assignment fraught with trap doors, two-way mirrors, and shackles. Some writers even disdain their subjects. Others hopelessly suck up to the person, if living, in hopes of winning their favor.

Journalists working the genre, however, are usually after something more. They took on the life of an individual because they believe — through professional research and interviews — that they can add more color or depth to what’s known about the figure’s public and private lives.

Today’s Mr. Media guest, Larry “Ratso” Sloman, has trod the path of biography and ghostwritten autobiographies a number of times in his career.

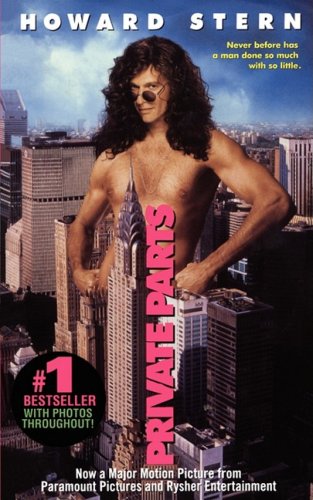

He wrote Steal This Dream about the life of 1960s dissident Abbie Hoffman. He helped Howard Stern pen his life story in two memorable books, Private Parts and Miss America. When Anthony Kiedis of the Red Hot Chili Peppers needed someone to help tell his story, Kiedis turned to Sloman.

The book many people remember Sloman best for, however, may well be his chronicle of Bob Dylan’s remarkable 1975 Rolling Thunder Review concert tour, On the Road with Bob Dylan. That is also where he earned his unusual nickname, which I’m told he wears with pride like a badge of courage.

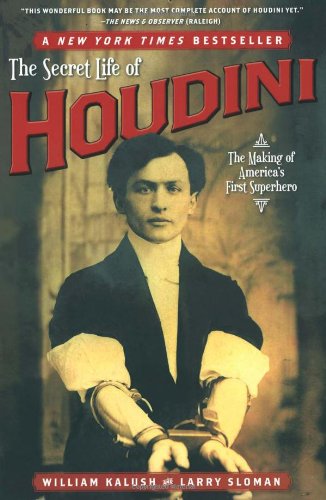

Sloman’s latest book, written with William Kalush is The Secret Life of Houdini, the Making of America’s First Superhero.

Larry “Ratso” Sloman Website • Twitter • Wikipedia • IMDB • Order Horward Stern’s Private Parts from Amazon.com

BOB ANDELMAN/Mr. MEDIA: Houdini is a fast read, thanks to the focus on storytelling and the wealth of incredible detail that you and your partner uncovered about the magician and the man. Can you tell us a little bit about how the book came about and the style in which it’s written?

LARRY “RATSO” SLOMAN: I first got interested in magic when I co-authored or ghostwrote — David Blaine’s memoir, Mysterious Stranger. It was a hybrid book. That book was part reminiscence about his various stunts and being encased in ice and being buried underground. It was also part teaching you how to do some magical effects, and it was also a kind of history of magic. For the history part, David said, “You have to go work with Kalush, because he produced all my shows, and he’s got the most amazing magic library in the world.” So we spent a lot of time at Kalush’s library, the Conjuring Arts Research Center.

We did all this research, and we did a chapter on Houdini in the David Blaine book. That was my first exposure to reading about Houdini. I read all the extant biographies of Houdini at the time, and I remember sitting around with Kalush and saying, “You know, it’s really strange. I mean, there are all these gaps in Houdini’s story, and he makes strange career choices. I think there’s more to this than meets the eye.” And Kalush says, “I agree.” And the more we looked into it, the more we said, “It’s time to take a fresh look at Houdini,” and that’s the genesis of The Secret Life of Houdini.

ANDELMAN: What about the storytelling? What I really like about the book is that every page is almost a separate anecdote in some ways in that you’re always storytelling. It’s not so much analysis, which some people expect in biography, but it’s storytelling, which is what I expect, and I really like that.

SLOMAN: It’s funny the way we wrote this book. In a way, we almost wanted to do a celebrity biography of Houdini akin to the ones I had written with Howard Stern and people like that. We wanted it to be accessible; we wanted it to be anecdote driven. There was a professor at NYU, Silverman, who had done an exhaustive biography, which kind of laid out a lot of the facts, and yet it really didn’t. The story wasn’t driven by these anecdotes, and to us, that seemed the best way to capture Houdini. He’s such an incredibly complex guy.

ANDELMAN: You did a tremendous amount of research in terms of organizing stuff that was arcane and seemingly unconnected.

SLOMAN: Thanks to what we lovingly called, “Ask Alexander.” It was based on Alexander the Mentalist, and what we did was create a huge, huge database. We scanned in every known Houdini book, all the magic magazines that Kalush had in his collection, all the letters, and all the scrapbooks, and made them text searchable. The book could have taken 25 years to write if we weren’t able to really have that instant access. This research project was over two years. So at the beginning of research, you may come across a name. A year and a half later, you may come across that name again and say, “Wow, I think this guy has something to do with…” Well, we just put the name into the database, and boom, in five seconds, we had every hit on that name. It was a tremendous expedient. I think it’s really the first Houdini biography of the digital age, and we were able to collate all this incredibly diverse material.

ANDELMAN: Now, a lot of writers — and Doris Kerns Goodwin comes to mind — have been in trouble the last couple years with issues of plagiarism. I’m not saying that you did this, but my question is, when you scan in material like that, how do you avoid that? I mean, Doris’ comment was, “It was inadvertent that I used material from another source,” but when you go to this digital type of system and you scan in all this stuff, it would seem like the situation is ripe for that kind of abuse

SLOMAN: Our book is full of citations. We very liberally use Houdini’s own writings. We use letters that he had written. I don’t think the problem so much is plagiarizing anything, because the analysis that we did was almost separate from the writing process. We overlaid the analysis onto the writing, and the analysis was basically between me and Kalush, who was the magic expert. So if there was a question of how Houdini did something and we wanted to reveal that, and a lot of times we didn’t reveal that, obviously. But there were times where we did reveal some of his methods, and that was overlaid after the main narrative had been written already.

ANDELMAN: Will the way that you used technology to research this biography affect the way you do it in the future?

SLOMAN: Absolutely. I mean, I think there’s no other way to do it. It’s so overwhelming to have that amount of material, but when you have it in a way that’s manageable and that literally you can do searches in microseconds … All the major newspapers now have their entire archives in databases. We were able to find out a lot about John Wilkie, who was the head of the Secret Service and whom nobody really knew anything about. We were able to find out his connections to the world of magic through an article in the Washington Post in 1908, because of this new technology. It is certainly an incredible boon. I’m sure we would never have been able to find those articles if not for that.

ANDELMAN: I think one of the most controversial revelations in the book is Houdini as a spy.

SLOMAN: It’s funny. It was controversial at first. The magic world is very insular, so a lot of these guys were saying, “We don’t know about this, so therefore it can’t be true.” But when you get a guy like the former head of the CIA, John McLaughlin, who reads the book and says, “Yeah, I’ll write an introduction to your book,” and says in the introduction, “This is absolutely plausible to me.” So

I don’t think you could have anybody better vouching for your theory than the former head of the CIA.

ANDELMAN: Absolutely. Well, it’s a great read, and I hope it’s doing well, and I hope more people will read it.

SLOMAN: Well, it’s doing well, and in fact, the latest wave of unbelievable press and attention has been the whole exhumation thing, and that was based on our research. It was one of these serendipitous things.

Two years ago, I attended the annual Houdini séance that Sid Radner, a Houdini scholar and collector, puts on every year. That year, it was in Las Vegas, because he was also auctioning off a lot of Houdini material. At the séance, there was the great-granddaughter of Margery, the world’s most famous medium at the time, who was Houdini’s adversary in the last years of his life.

I approached her. It turns out she lives in Long Island not too far from where I have a weekend place, so I said, “Could I come and interview you?” figuring that there may be some great family anecdotes about Margery and Houdini, and she said, “Sure.” And I go to visit her and her husband, and they make me a nice dinner, and we have a great interview, and at the end of the interview, I said, “You wouldn’t happen to have like some letters or any kind of documents laying around?” She said, “Oh yeah, come on.” And she takes me into a spare bedroom, and she opens up the closet door, and the entire closet is filled with boxes and boxes of correspondence, including correspondence with Arthur Conan Doyle, Sir Oliver Lodge, all the leading luminaries of the spiritualism movement. It’s got over thirty scrapbooks of Margery that were amassed by her husband, and nobody had seen this material for 80 years except for her and her mother.

My jaw dropped. I wound up spending the next two weeks over there every day. She was such a doll, she even helped me carry the material to the local store to Xerox it. Those thousands of pages were then put into the Alexander, made text searchable. From that material, we developed the most compelling part of the book to me, which was the last few years of his life and how the battle with the spiritualists may have ended with Houdini’s death at their hands.

LARRY ‘RATSO’ SLOMAN podcast excerpt:“We don’t say for sure that we definitely think he was murdered, but we raise enough issues about it that Houdini’s grandnephew read the book and said, “I want to get to the bottom of this.” It means we would have to exhume his body and test for poisoning.”

While we were writing the book and talking about the last few years of his life and the medical problems at the end, we had consulted Dr. Michael Baden, who is one of the great forensic pathologists in the country, in the world. Baden called a friend of his, a colleague, Professor James Starz at George Washington University, who’s a dual professor in law and forensics. This is a guy in cases where, to solve a murder mystery or things like that, he has exhumed some very famous people. I sent him the book on Baden’s recommendation. He read it, and he said, “You guys have really raised enough issues — sign me up, I want to get involved in this.” He has amassed an amazing team of forensic scientists — two anthropologists, two toxicologists, two of everything because he is very thorough, two pathologists, including Dr. Michael Baden. The team is all set, and now it’s just a matter of going through the legal motions. It’s tremendously gratifying to us that the research that we came up with could lead to the world’s leading forensic scientist to say, “I think you guys really have something here. Let’s look into it.”

VIDEO: Sloman and co-author William Kalush discuss Houdini

ANDELMAN: It’s one thing to collect history, but then to suddenly find yourself affecting history has got to be very rewarding.

SLOMAN: People say to me, “What difference does it make? It was 80 years ago; whoever killed him, if they did kill him, is long gone.” What difference does it make? I think it makes tremendous difference, because if Houdini died fighting the spiritualists who, in his mind at that time, were Public Enemy No. 1 because they were preying on the most vulnerable people in society, people who had recently lost loved ones and were desiring to get in touch with them, and these people were manipulating and conning and bilking these people out of tremendous amounts of money, and if Houdini wound up being murdered by them, then he died a hero’s death. He was not just one of the world’s greatest entertainers, but his life assumes heroic proportions.

ANDELMAN: I want to ask you one more thing about Houdini, and then there are some other things I want to talk about. I suspect that what a lot of people know about Houdini comes from the movies, Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh for the old-school gang or Paul Michael Glaser and Sally Struthers for my generation. I wondered if you had a preference now among the portrayals?

SLOMAN: I don’t think any of them have really captured Houdini. In fact, the worst was the Tony Curtis film, because that’s a passive-aggressive example of how Hollywood could defame a legend. They have Houdini dying in one of the devices of his own making! But Houdini became a superman to people because he could never be constrained. That was his whole shtick, and every night, he would be tested, he would be challenged, whether it was handcuffs or leg cuffs or put in a box, put in a safe, inside a giant football, or inside a big whale. I mean, no matter what it was, he got out, and to have Hollywood killing him in his own water torture was the worst.

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

Leave a Reply