Lee Salem is a guy I’ve admired for many, many years. As the president and editor of Universal Press Syndicate, he is the man responsible for recognizing a slew of creative talent that impacted American pop culture and the funny pages over the last 30-plus years. The origins of Garry Trudeau and “Doonesbury,” Gary Larson and “The Far Side,” Bill Watterson and “Calvin and Hobbes,” Lynn Johnston and “For Better or Worse” and Cathy Guisewite and “Cathy,” all can be traced back to the man I’m about to interview.

I had my own up-close and personal moment with Lee Salem. Mr. Media was originally a weekly syndicated column, one distributed by Universal Press Syndicate from July 1996 to May 1998. I remember my first email from Lee, suggesting Universal was interested in distributing the column, which until then had been self-syndicated. He even invited me out to Kansas City, where I met a half-dozen people – including Sue Roush, Bill Mitchell and Darrell Coleman – who I stayed friendly with for many years to come.

And on that trip, seeing how awed I was by whom I was with and my surroundings, Lee jokingly invited me to take a spin in his office chair. Who could resist? Would a political junkie refuse the chance to sit in the President’s chair at the Oval Office? Would a Trekkie turn down the opportunity to take the con from Captain Kirk? It was a pretty cool ride for a guy who dubbed himself “Mr. Media.”

I like Lee a lot and respect him even more. And when I decided to restart Mr. Media as an online feature, Lee Salem was at the top of the list of people I wanted to interview.

Universal Press Syndicate • GoComics • Blog • Twitter • Facebook • Instagram

BOB ANDELMAN: Lee, thanks for taking the time to do this.

LEE SALEM: I enjoy it.

ANDELMAN: Not a bad introduction, huh?

SALEM: Pretty good.

ANDELMAN: Let’s start by playing a game of first impressions. Tell me what you remember, the first thing you remember about these things that I mentioned, if you would. Let’s start with “Doonesbury.”

SALEM: Well, a slight correction. “Doonesbury” was picked up by the syndicate in 1970, and I started in 1974, but it wasn’t more than a year and a half or two when I started editing Garry. One of my earliest recollections on the bad side was letting the word “missile” to through misspelled, a word I will never misspell again. And on the good side, I started in July of 1974, and the following spring, we nominated him for the Pulitzer for his work in 1974, which mostly focused on Watergate. And that year, he won his Pulitzer, so that was a thrilling time for all of us.

ANDELMAN: All right. And what about “The Far Side”?

SALEM: We had been doing Gary’s books for maybe a year or so, and Gary at that time was with a smaller syndicate, Chronicle Features, and made it clear that he wanted to come over to us, and we had some tough negotiations with his lawyer, and Bob Duffy, who preceded me in the presidency and was then sales director, and I kind of looked at each other wondering about the tough terms of his contract, but it worked out great for everybody, and we had a wonderful run with Gary and still do calendars with him on a regular basis and still remain friends.

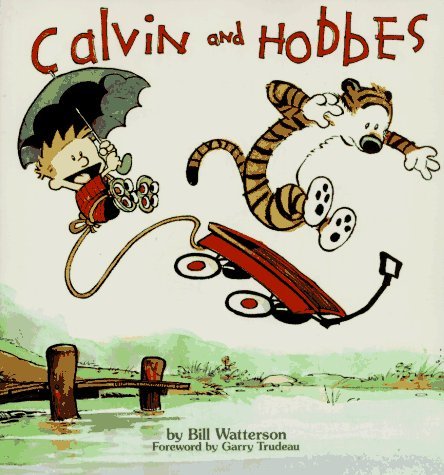

ANDELMAN: “Calvin and Hobbes.”

SALEM: Well, Bill is Bill. The somewhat rancorous relationship between the two of us, while occasional, was still public, and he made his feelings clear about the business obligations that we felt and thought that we were asking too much of him and “Calvin and Hobbes” in terms of exposure in the market. We ultimately accepted his arguments and redid his contract, and he retired after a brilliant ten-year run, probably as strong a ten-year run as anyone in comics history, I think.

ANDELMAN: “Cathy.”

SALEM: Well, we just celebrated thirty years with “Cathy.” We had a nice dinner with her last fall. When “Cathy” began, everyone was apprehensive. We circulated it in the office before we launched it, and people were saying, what is this, the art and the character? And it is still in well over a thousand papers after thirty years, which, in this market, is quite an accomplishment. I really look on her as a pioneer, and if “Cathy” had not worked the way we hoped it would, I am not sure we would have made the plunge with Lynn Johnston and “For Better or For Worse.” But “Cathy” worked, and it seemed natural to us that the time was right for talented women on a comic page.

ANDELMAN: All right. Well, then, “For Better or For Worse.”

SALEM: Well, that’s a great segue. When we saw Lynn’s work, we loved it. We loved her perspective. In the late ’70s, there was not a great demand for more family strips because the pages seemed to be dominated by them, but what attracted us was the mother’s perspective and the somewhat wry tone she would take on her situation and her husband’s life and children’s lives, and it has proven to be a comic strip that has dominated the surveys in terms of popularity for a long time.

ANDELMAN: And another family strip, “Foxtrot.”

SALEM: It’s a wonder Bill even signed with us. When Jake Morrissey, who was an editor with us, and I first visited Bill out in California, we had breakfast with him and went outside and went to wish him well, and somebody had taken off the bumper on the front of his car, and we had to dash off because we had another appointment. We were in Berkeley, and there was a comics convention then, and we kind of left Bill there. We waved at him and wished him well, and ever since then, I have felt terrible about it, but “Foxtrot” was another case of, answering the question, does the world need another family strip, but the kids were so different, and he was bringing in science, and that occasionally kind of added another perspective to it, and really, until his retirement from the daily portion of “Foxtrot” a couple months ago, I think it was consistently a top ten strip.

ANDELMAN: We just have a couple more. I promise I am not going to take you through the whole list. “The Boondocks.”

SALEM: Well, “The Boondocks,” for a long time we had been looking for a strip by an African-American cartoonist, and nothing really leaped out to us as saying this is a Universal-type strip, and then “The Boondocks” landed on our desks, and one of our editors in Chicago spotted it. He sent in a submission to us about the same time. Everyone had a very similar response that this was a breath of fresh air, and it proved out to be a wonderful strip for us. It didn’t achieve in number as some of the strips we have already mentioned, but in terms of its notoriety, it certainly was a national phenomenon, and he used that to springboard to what we hope will be a successful career in animation in television.

ANDELMAN: “Bloom County.”

SALEM: Not one of ours.

ANDELMAN: I know.

SALEM: But Washington Post Writers’ Group. I have been a long-time admirer of Berke’s work and met him a few times in social situations. I think he tried assiduously to get away from the mantle of being a derivative of “Doonesbury,” and I think to some extent he succeeded, because I think the characters and sensibility developed to be pretty much his own.

ANDELMAN: And the last one, “LIO.”

SALEM: “LIO” is a new strip, has been out less than a year, and it is something different. There is no language in it, it’s all pantomime, which I suspect is very, very difficult to do from the creative standpoint trying to think up a new situation each day using this character as the focal point. It’s a little dark and edgy sometimes though oriented for younger readers, and we have had a terrific launch with it, and it’s approaching 300 papers in less than a year, so we are delighted with it.

ANDELMAN: Oh, is it up that high already?

SALEM: Yeah.

ANDELMAN: I spoke to him a month ago, and it was at 250.

SALEM: Well, it’s at 275 or 280 now. He did benefit somewhat by “Foxtrot” going off the daily pages, but I think we will have a good long run with it.

(Return to Part 1)

ANDELMAN: We talked about “The Boondocks” a minute ago, but do you think that Aaron McGruder will ever return, and what was the last you heard about this?

SALEM: I know he is enamored of the whole Hollywood sensibility and the opportunities of Hollywood. I think he thinks that he can do a bit more creatively with animation, and I certainly understand that. I think that there are certain personality/creative types who are drawn to what comic strips can do whether on a newspaper page or the web, but I think other sensibilities respond to animation. I think Aaron’s talents are shown on a television show, and I doubt very much if he will return to the confines of a three or four panel a day strip.

ANDELMAN: Have you ever thought what it is that might be different about the culture at Universal compared to other syndicates, that, you have had these brilliant strips, these very unique strips, whether it be “Far Side” or “Calvin and Hobbes,” “Boondocks,” even “Doonesbury,” which has taken some long breaks? You don’t hear these same kinds of things happening at other syndicates. I mean, we never heard about Fred Laswell taking a year off from “Snuffy Smith,” for example, or giving up a popular strip like “The Boondocks.” Why does it seem to happen at Universal whereas we don’t hear about it from other syndicates?

SALEM: Well, the owners here asked me the same question with a slightly different tone in it: “Why is that happening to us all the time?” I think when the company was founded by John McMeel, who is now the CEO, and Jim Andrews, who ran the editorial side and, alas, died in 1980, I think they wanted to do things a little differently, and even in a very conservative medium like the comic page, tried to push out the boundaries a bit, and I think that is the flip side of the coin of being attracted to talents who are somewhat exotic and eccentric in the way they approach the art form. Garry, I think, really was the cornerstone of the editorial viewpoint that we had developed. We like people who try to do things a little differently, and sometimes that entails a slightly different attitude toward the definition of a career. You’re right. There are other cartoonists, and they are legion, who wouldn’t think about taking time off. I think when we announced a vacation program for our cartoonists, Charles Schulz was quoted as saying, “Well, I love this job; why would I ever want to take a vacation from it?” But I am not in a position to judge another person’s creative wellspring, and if our cartoonists sometimes think they need some time off, then we are going to try to accommodate them within certain limits. I think it’s the responsible thing to do for the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and I think if we had not had a time-off policy for someone like Trudeau, I think he would have given up the drawing board a long time ago.

ANDELMAN: Do you think that Universal has kind of looser reins on its artists than maybe others do?

SALEM: Yeah, that’s one way to describe it. Editorially, we are involved quite a bit. We spend a lot of time up front working with cartoonists on characters and development and trying to come up with a common understanding of where the strip might go in the future. I think that we have a reputation for standing with our artists. I think that’s a good thing more often than not, and I think that the artists respect us and like us for standing with them when they try to do something that is perhaps frowned upon by some newspapers. But in terms of loose reins, I am not sure if I would describe that, because we believe in the creative process, and we believe that the cartoonists, once they have developed a relationship with their readers, have a right to try certain things, and maybe it’s not so much a question of tight or loose reins but a different approach to creativity and how that is going to be reflected in the marketplace.

ANDELMAN: Lee, as you look back, if you would look back on Lynn Johnston’s separation from Universal, is there anything you wish you had done differently? And the reason I ask that is that was a tough time to lose a strip that had, I think, 1,800 clients, given that you had just lost, I think, within a period of time Watterson, Larson, and Erma Bombeck had died on the column side.

SALEM: Yeah, that was in a relatively short space of three years or so, and those are four people who left us for different reasons. Yeah, looking back, I am sure that there are things we could have done in our relationship with Lynn that would have encouraged her to renew with us. She decided she wanted to try something else, and we always know that the grass is greener on the other side of the fence, and in this case, it wasn’t as green as perhaps she thought it was. It wasn’t too long into it before she called and tried to renew the relationship, and when the opportunity afforded itself contractually, she came back to us.

ANDELMAN: In terms of, and we should include her in the group we were talking about a little while ago about the kind of looseness of taking time off, who came up with the new plan where some strips will kind of repeat, and it’s going to be not fresh every day, or maybe you would want to describe that differently?

SALEM: Well, she has a very able team who works with her on different aspects of the strip and also assists her with licensing and other areas, and I think that in discussions up there, they kind of were moving toward this approach to the strip, and when it was presented to us, we talked about it and had some input here and some input there, but to us, it seemed like a nice midway point between either full retirement or keeping up with the daily grind of deadlines. So we are looking forward to seeing what happens, because I think it will be a blend of old and new, and I think it will be something a little different in the market. It won’t be strict reruns as such, and I think she is going to take some creative steps that this particular approach will allow her. I think it’s going to be good for newspapers and good for fans in newspapers and probably good for the strip.

ANDELMAN: And when will that start?

SALEM: Late September.

ANDELMAN: Okay. Let’s come back to “Cathy” for a moment. I was reading something that interested me. Cathy Guisewite had said that she was originally encouraged by her mother to become a cartoonist, that her mother went to the library, made up a list of syndicate editors to whom her daughter, who was kind of hesitant, should submit her admittedly maybe primitive drawings, and the first name on the list was you. Do you remember that package?

SALEM: I still have that package.

ANDELMAN: Oh, you do?

SALEM: I remember it very well. When I retire, it will be on eBay. It was one of those things, it was addressed to Jim Andrews, whom I have already mentioned, and at that time, the submissions came in to me, and it ended up at the top of my “In” box, and just by fluke, I just grabbed it and immediately loved the writing, and I put a little note on it saying, “I really love this writing, but the art…?” And it went to my out box, and that same day it ended up in the top of Jim’s in box, and he just happened to grab it, and we had a contract out to her the same day. And that’s what’s fun about this business is that things like that can happen. It’s still a great forum for Cinderella stories, and there is a talent out there yet who could send something in and six months later be in a hundred papers and a year from now be in 300 or 400 papers. It can happen that quickly, so it’s still a lot of fun, and that’s what keeps us going.

ANDELMAN: Which is more important, though, the art or the story-telling?

SALEM: Well, I think the times have shifted. People like Garry Trudeau and Cathy Guisewite, even some of the early Larson, the art was criticized by more established or more finished artists, but I think in those cases, the writing really kept things going until the art could catch up to the writing. I think now that we have been through that period of thirty, thirty-five years, “Dilbert” is another good example, I think that given readers’ habits and what newspapers are looking for, good writing will prevail over good art. I think it’s easier to sell good writing with less good art than it is to sell good art with less good writing.

ANDELMAN: I think I know the answer to this next question, but I am going to ask you any way. Cathy appears in easily more than a 1,000 newspapers, but it doesn’t get the same respect that some of your other strips do. As a matter of fact, it is often ridiculed in other strips. How do you explain its enduring popularity?

SALEM: Well, I think it is in some ways an iconic strip. I mentioned before that I thought in some ways she was a pioneer in this industry, and outside of “Brenda Starr,” which wasn’t really a humorous strip, and one or two earlier attempts, there really was not much in the comics pages for or by women in 1976, and this was the year in which, I may be off a year or two, but I think women were the people of the year at Time magazine. We were kind of waking up to the fact that half of our population really wasn’t being given opportunities the way they should be given, and I think “Cathy” was perceived as an example of that at that particular point. I think within a year and a half or two years of syndication, she had been invited to the White House and was involved in efforts for the Equal Rights Amendment, and I think that her long-time readers have come to accept that part of what she did for the art form and for newspapers. I think more recent readers look at the strip a little differently in terms of the small world in many ways that “Cathy” inhabits, but the writing has been consistent over the years, as has the art, and I think people have just come to accept what it is. You’re right. Some of her fellow cartoonists sometimes make fun of her style or the way she sets up jokes or the themes that she explores, but what’s interesting, I think two springs ago, she was honored by the National Cartoonists’ Society, and some of those very same cartoonists who might on occasion ridicule the strip were the first ones in line to shake her hand and give her a hug and ask for her autograph.

ANDELMAN: You have mentioned Cathy Guisewite as one of the first female cartoonists doing a daily and female-centered strip that really hit it big and then also seeking out an African American-based strip in “The Boondocks,” I recall that “For Better or For Worse” got you guys in some hot water at one point when — is it Lawrence? — who turned up gay? Are there any gay strips coming? Should there be?

SALEM: I haven’t seen any. I think that if that’s going to work, it would be less because it’s a gay strip than it is because it is a strip with characters, one or two of whom happen to be gay, if you see the emphasis difference there, but who knows? It would depend a lot on the writing and the sense of humor that the artist might employ.

ANDELMAN: It would be a lot trickier, I bet, to get that on the daily newspaper pitch. If you could point comics fans to one largely undiscovered Universal strip, what would it be?

SALEM: Oh, gosh, there are too many people that… I am looking at my wall. One of my favorites is from a panel we do, and the answer shows a guy standing there on the phone, and he goes, “Uh oh,” and the caption is reading… wait, it’s way across the wall… the caption says, “You find out that you are responsible for things you never knew you were responsible for,” and that’s the kind of humor that I particularly like. You are going to have to edit this. I am blanking out on the title of the panel.

ANDELMAN: I like that, actually.

SALEM: It will come to me before the interview is over.

ANDELMAN: All right. And if it doesn’t, you can tell me later, and I will add it in. Now, what strips distributed by your competitors would you like to have had a Universal?

SALEM: You know, I spend more http://www2.blogger.com/img/gl.link.giftime thinking about what we’re doing and less about what the competitors are doing, so I am not really sure how to answer that. Obviously, any syndicate executive would have loved to have “Dilbert” before it took off the way it did, and there are other strips that are making a mark, like “Pearls Before Swine” and “Get Fuzzy.” But you know, I just finished reading a book called April 1865, which is about the last month of the Civil War and the assassination of Lincoln, and there is a scene in which Grant is talking to his generals, and he said, “Lee, Lee, I am tired to hearing about General Lee. What are we going to do?” And that’s kind of like the way I look at it. I worry less about the other syndicates are doing than what we ourselves are doing.

ANDELMAN: Well, let me ask you in a slightly different way, and you already mentioned…

SALEM: “Real Life Adventures,” by the way. It suddenly came to me.

ANDELMAN: That’s it, “Real Life Adventures.”

SALEM: “Real Life Adventures” is one of my favorite panels.

ANDELMAN: Okay. Now, Will Eisner used to tell a story about rejecting “Superman” when Siegel and Shuster were shopping it to New York publishers in the last 1930s. Do you have any similar stories of missed opportunities? You kind of referred a little while ago to “Dilbert.” I wondered if that might be one.

SALEM: I don’t know whether we saw “Dilbert.” We did see “Bloom County” early on, and he signed with the Washington Post Writer’s Group. The story’s here that somebody may have seen “Garfield” way back when, but I can’t confirm that one. It’s a small enough industry with only half a dozen or so major players that it wouldn’t surprise me if we saw one or two others that were picked up by the syndicates and did very well, and vice-versa. It happens in this business a lot, maybe not a lot, but it happens enough so that syndicate editors who are in charge of acquisitions are certainly aware that it’s a problem, and we try to be sure to look at things quickly when they come in.

ANDELMAN: How many submissions a year at this point?

SALEM: We get roughly fifty or sixty a week, so that’s 3,000 or so a year. Not all comics, of course, but a mix of things, puzzles and columns, etc., but everything has to be looked at to be sure that it’s something that we can use or not use.

ANDELMAN: I imagine you might have some good stories, but to what lengths have creators gone to get noticed by you and Universal?

SALEM: Well, there are some who just knock on the door and say, here I am, and sometimes we can see them, sometimes we can’t, depending on what’s going on. I do remember one person had a strip set on a tropical island. I forget the details of it, but for a week we were getting coconuts in the mail in advance. We would open this coconut and no note, no anything, and then maybe the third day there was a note, and by the fifth day, it was like, coming soon, and then we finally got the submission, so that was a creative way to do it, and we looked at it, but there wasn’t something we thought we could do much with. But I think people rely too much on fancy packaging and less on writing and art in the original material, and that’s the one thing I would encourage people interested in the art form, is to spend time on the writing, spend time on the art work, and then don’t worry about the quality of the package. Assume that the editors are going to do their job and read the material.

ANDELMAN: Lee, before we wind up, just a couple more things. Universal, of course, distributes far more than comic strips. It was the home of Erma Bombeck, it distributed my pal Chuck Shepherd’s popular “News of the Weird” feature, and it’s the home of conservative columnist Ann Coulter. Are there any internal conflicts being the distributor of political properties as diverse as Garry Trudeau and Aaron McGruder and Ann Coulter?

SALEM: Not so much conflicts. It’s interesting you would mention Ann Coulter and Aaron McGruder, because at one time, the same editor handled both, and I think he suffered from political whiplash if he had a week of “The Boondocks” come in the same day as a column by Ann Coulter, say. I think that newspapers and readers understand that syndicates are in the business to disseminate entertainment and disseminate ideas and disseminate discussion, and it would not do this company any good, nor do I think it would do newspapers any good, for us to come have a strong ideological viewpoint, personal strong ideological viewpoint that we try to purvey in the newspapers.

ANDELMAN: And I know that Universal has had some events, I guess the 25th or 30th anniversary, have those three ever been in the room together?

SALEM: No.

ANDELMAN: Okay. All right. I realize that Aaron, of course, is not doing “The Boondocks.” Is it still running in some places?

SALEM: We make it available online and in print for foreign newspapers.

ANDELMAN: Which of the three, Trudeau, McGruder, or Coulter, has caused you more sleepless nights or phone calls from nervous editors?

SALEM: Well, all three have presented a variety of problems, but I would have to put Garry Trudeau at the top of the list, only because that’s about as close as we ever came to getting sued. He did a week on Frank Sinatra receiving the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor that an individual can receive, and he did a week on Sinatra, just a blistering week, with alleged Mafia ties, etc., etc., and we had lawyered it inside, out, and backwards, and but that didn’t stop Sinatra and his lawyers, and we had some exchange of mail, and I really thought that this could be it, this could be the test of the First Amendment, but finally Sinatra’s lawyers backed off, but it was touch and go and our lawyers in the situation were terrific. The people we got problems from, of course, was the insurance company.

Nice interview.