Today’s Guest: Dennis O’Neil, writer, editor, Batman comic books

(Originally published around 1996.) Is it fair to speak the word “Batman” in the same breath as Hamlet?

“There is no one right way to do this character any more than there is one right way to do Hamlet,” insists Dennis O’Neil, editor of nine Batman and Batman-related titles for DC Comics. “I realize I’m beginning to sound pretentious, but there are a lot of ways to play Hamlet; there are a lot of ways to play Philip Marlowe to get more contemporary. These characters last because something in them strikes a responsive chord in a lot of people.”

Bob Kane may have created Batman, but that was 57 years ago — ironically, the same month, May, and year, 1939, O’Neil himself was born. “Enough to make you believe in astrology,” he jokes. For the last 11 years, the caped crusader’s care and feeding has rested with O’Neil.

O’Neil knows this character pretty well, too, having written more than 120 of his adventures since 1968. One of the modern deans of his medium, O’Neil wrote the “Bat-bible” which all Bat-writers have followed for the past decade, whether in comics, animation or film. He also authored the comic book adaptation of the upcoming Bat-film, Batman & Robin, due in theaters this summer.

Also on O’Neil’s resume: he has been a guiding force in introducing social issues to comic books, from writing the now classic “Green Lantern-Green Arrow” series on drug abuse 25 years ago to shepherding this month’s focus on date rape in the pages of “Robin.”

DENNIS O’NEIL podcast excerpt: “We gave the book psychological underpinnings. They were always implied in the whole idea of Batman, but what we did was bring it to the foreground and put emphasis on them.”

The name of Hamlet came up when O’Neil was asked about the current condition of the Dark Knight, who has weathered permutations ranging from the campy Adam West TV show of the 1960s to the dark and dreary Tim Burton movies of the 1980s. A very different Batman appears in the current cartoon series, “Batman, The Animated Series.”

“Any time you take something from one language to another or from one medium to another, you have to really rethink it,” O’Neil says. “The Batman cartoon universe is different from the comic books and our Batman is different from the movie universe. I think if I were a disinterested observer, I would find it interesting to see diverse interpretations of this same idea.”

O’Neil first spun the character in the months following the cancellation of the ABC “Batman” series in 1968. Since then, Batman and Bruce Wayne’s world has been a dark and tortured place.

“We gave the book psychological underpinnings,” O’Neil recalls. “They were always implied in the whole idea of Batman, but what we did was bring it to the foreground and put emphasis on them.”

The Caped Crusader turned completely humorless and bleak in 1993 when a bad guy named Bane broke his back and nearly killed him in a year-long story called “Knightfall.” That incident led to the arrival of a violent new Batman named “Azrael” and an updated costume outlined by sharp edges and an arsenal of high tech new Bat-gadgets, all of which were roundly booed by readers.

O’Neil says that trying out someone other than Bruce Wayne as Batman was a product of the times in which we live.

“We wondered if our notion of hero was outmoded,” he says. “Looking at other media, not only comics but popular movies, heroes seemed to be not a whole lot different than the villains in that sometimes the only qualification for heroism that the hero seemed to posses was the ability to commit wholesale slaughter and wisecrack about it. Which is antithetical to my idea of hero. I’ve always thought physical prowess has to be balanced by some kind of soul.

“We’d been wondering for a long, long time, with his stricture against killing and his Boy Scout morality, if our hero was outmoded,” O’Neil continues. “So instead of continuing to avoid the question, we decided to confront it and put out there a Batman who was as genuinely nuts as our Batman was sometimes accused of being.”

Throughout that stunt, O’Neil’s greatest fear was that readers would actually like the Azrael Batman. “I don’t know what exactly we would have done,” he admits. “I might have schemed myself out of a job.”

But readers hated Azrael in the role.

The storyline consumed 1,164 pages by O’Neil’s count — more than a year in real time — before Bruce Wayne once more donned his traditional cowl.

“It validated the kind of heroic ideal that Batman has always represented,” O’Neil says. “And it told me that at least as far as our audience is concerned, although they may applaud and enjoy the bloodletting, slaughter-type characters at the movies, they could still appreciate an older, nobler idea of what a hero is.”

That’s why Batman keeps coming back, stronger and ever more intriguing, while his friend Superman struggles through marriage, a ponytail and an electric-blue new costume and powers.

“I think Batman attracted more really good talent over the years,” O’Neil says of a perceived creative disparity between the two characters. “Having written both characters, it was that invincible thing that made it difficult for me to handle Superman — both to identify with him and to write dramatic stories. The nature of melodrama is that the hero has to be in really bad trouble once in a while. There must be conflict and conflict implies that he goes against equals. That’s simple, Basic Writing 101. I always found it easier to fulfill those requirements with Batman.

“One of things you heard as an undergraduate 40 years ago was ‘Write what you know,’ ” he says. “Well, I’ve never stood on a rooftop at 3 a.m., waiting for a grotesque maniac to show up. If I had, the New York Post would have covered it. I think the germ of truth (in Batman stories) is implied.”

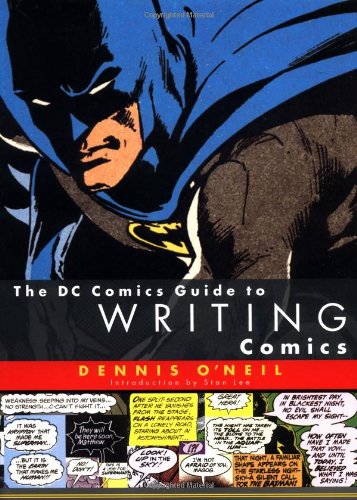

Dennis O’Neil Wikipedia • Facebook • Order The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics from Amazon.com

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!